A Psychological Reading Of The Film Shutter Island

Some films do not end when the final scene fades out. Their stories may conclude, but the questions they raise linger in the mind. Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island is one such film. Beneath the surface of a criminal investigation, the narrative gradually pulls the viewer into a deeply internal terrain. What is examined here is not a crime, but a mind struggling to endure reality.

A Mind Under Siege: Trauma And Psychological Confinement

The story begins in 1954, when U.S. Marshal Teddy Daniels and his partner Chuck Aule arrive at Ashecliffe Hospital for the Criminally Insane to investigate the disappearance of a patient. From the outset, the island conveys a sense of psychological confinement rather than mere physical isolation. Storms, locked doors, and unanswered questions slowly shift the focus from the external world to the protagonist’s inner life.

Teddy Daniels appears as a man heavily burdened by his past. His experiences at Dachau, the loss of his wife in a fire, and his recurring migraines all point to a fragile mental state. The film’s dream sequences and hallucinations—particularly the images of drowned children and the accusatory presence of his wife, Dolores—suggest that trauma is forcing its way back into consciousness. These moments reveal that trauma is not only remembered, but continuously re-experienced through affect, collapsing the boundary between past and present.

Repression And The Reconstruction Of Reality

From a psychodynamic perspective, repression plays a central role in Teddy’s mental organization. Yet the film makes clear that repression alone is insufficient. Teddy’s understanding of the events on the island reflects not only forgotten memories but also a reconstructed reality.

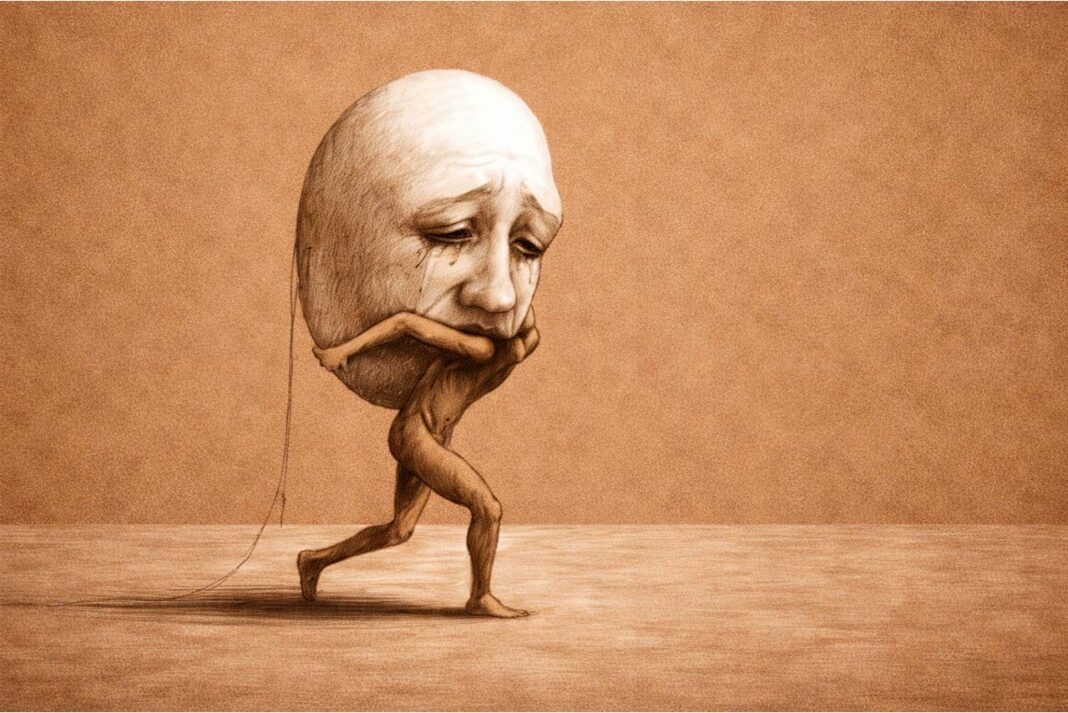

When the mind encounters experiences that are psychologically unbearable, it does more than suppress them—it reshapes them into a narrative that feels manageable. Defense mechanisms thus appear not as signs of pathology, but as attempts to preserve psychic continuity. In this sense, delusion is not chaos; it is structure.

The relationship with Dr. Cawley illustrates this process. Rather than confronting Teddy directly with the truth, Cawley adopts an approach resembling controlled confrontation. Reality must be introduced gradually; otherwise, confrontation risks psychological collapse rather than healing. The film subtly raises a clinical question: Is insight always curative, or can it sometimes be destructive?

Identity As Refuge: Teddy Daniels And Andrew Laeddis

The film’s pivotal revelation—that Teddy Daniels is in fact Andrew Laeddis—marks a crucial psychological shift. What matters here is not the change of name, but the function of identity. For Andrew, the persona of Teddy serves as a refuge from overwhelming guilt and grief.

The murder of his wife Dolores after she drowned their children represents the core trauma that shattered his sense of self. This process closely resembles what Winnicott described as the formation of a false self, in which an adaptive identity replaces the authentic self in order to survive psychic annihilation. Teddy is not a lie; he is a psychological shelter.

Throughout the film, Andrew repeatedly walks the same corridors, encounters similar situations, and obsessively searches for the truth. These repetitions reflect what psychoanalysis terms repetition compulsion—an unconscious attempt to resolve unresolved trauma that instead binds the individual to it. The mind circles the wound, not to heal it, but because it cannot yet bear its meaning.

The Therapeutic Alliance And Its Limits

Chuck Aule—later revealed as Dr. Sheehan—functions as both companion and therapist. His presence represents the therapeutic alliance, but also the limits of how much reality Andrew can tolerate. This dynamic underscores a painful truth in clinical work: not all patients can integrate insight, even when it is offered with care.

This leads to one of the film’s most unsettling reflections: Is living with the truth always possible, or does psychological survival sometimes depend on illusion? The final line Andrew utters before undergoing lobotomy—

“Which would be worse: to live as a monster, or to die as a good man?”

reflects a profound psychological decision.

Here, withdrawal is not ignorance; it is a choice. When reality becomes unlivable, the mind may choose containment over awareness, illusion over annihilation.

Conclusion: Survival Or Self-Betrayal?

Shutter Island offers no reassuring answers. Instead, it confronts the viewer with an unsettling reality: the mind is not only fragile, but also remarkably creative in its efforts to protect itself. The film is not simply a story about madness; it is a narrative of psychological survival, shaped by trauma, guilt, and identity.

And perhaps the most disturbing question the film leaves us with is this:

When the mind alters reality in order to keep us standing, is the person who remains still us?