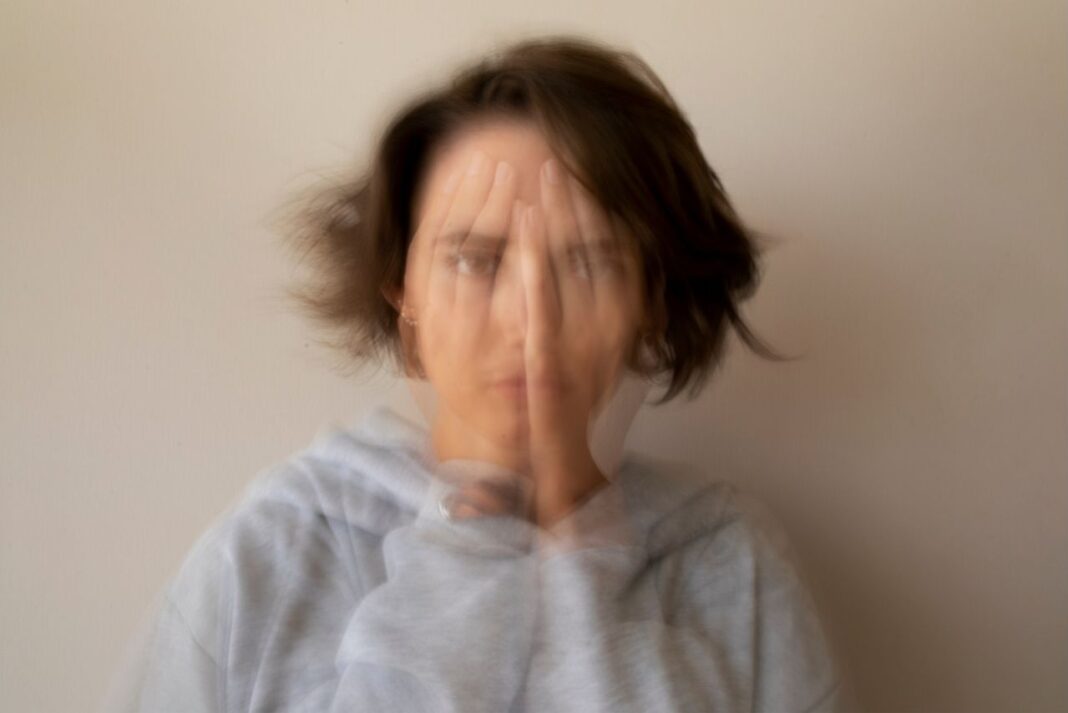

Anxiety can be defined as a state of apprehension, fear, or unease that arises when a person anticipates a situation whose outcome is uncertain or unlikely to occur. People often tend to deny, repress, or ignore experiences and emotions that create psychological discomfort. In doing so, they rely on defense mechanisms that disconnect them from both their internal and external realities.

However, these repressed emotions or unresolved psychological conflicts do not disappear. Instead, they resurface as persistent unease, restlessness, and anxiety that infiltrate daily life (Kring & Johnson, 2015).

When such unease and tension occur constantly—even in minor situations—this may signal the onset of an anxiety disorder. Over time, this excessive state of worry and fear contributes to both psychological and physiological dysfunctions, creating a vicious cycle that affects the entire mind-body system.

The Body’s Alarm System: The Biological Mechanisms of Anxiety

In individuals with anxiety, the sympathetic nervous system becomes hyperactivated, leading to a cascade of physiological changes. The body shifts into “fight or flight” mode, mobilizing its resources to confront perceived threats.

When a stimulus—internal or external—is interpreted as a threat by the amygdala, the information is immediately relayed to the hypothalamus, which in turn stimulates the pituitary gland. This chain reaction activates the adrenal glands, triggering the release of adrenaline and other stress hormones.

This process causes the following physical reactions (Şahin, 2017):

-

Increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration

-

Accelerated stomach and intestinal activity

-

Dry mouth due to decreased salivation

-

Elevated blood sugar through glucagon secretion

-

Dilated pupils and redirected blood flow from internal organs to muscles

-

Increased blood clotting and muscle tension

-

Hair standing on end (piloerection)

According to Cannon, anxiety arises from the organism’s effort to maintain internal balance (homeostasis). Failure to respond effectively to perceived threats—or to restore equilibrium—leads to the persistence of anxiety.

Similarly, Goldstein (as cited in Geçtan, 1978) explained that anxiety occurs when there is a mismatch between an individual’s capabilities and environmental demands. When this balance collapses, anxiety becomes an inevitable response.

Adaptive Anxiety vs. Pathological Anxiety

A natural response:

Anxiety is not inherently harmful—it is an adaptive survival mechanism. In situations involving uncertainty or risk (such as exams, job interviews, or major decisions), a certain level of anxiety can enhance concentration, increase alertness, and boost performance by stimulating adrenaline release.

A disorder:

However, when anxiety becomes prolonged, intense, and uncontrollable, despite the absence of a real threat, it transforms into a pathological state. At this stage, it starts to:

-

Disrupt daily functioning

-

Impair social relationships

-

Reduce overall quality of life

This type of chronic anxiety often results in a constant state of alarm, where the body and mind remain hypervigilant even in safe environments.

Physical and Environmental Triggers of Anxiety

Anxiety does not always stem from psychological causes; biological and environmental factors can also contribute:

-

Medications: Certain prescription drugs can heighten nervous system arousal.

-

Stimulants: Excessive caffeine consumption often increases heart rate and anxiety symptoms.

-

Poor nutrition: Unbalanced or insufficient diets can alter neurotransmitter activity.

-

Sensory overload: Loud noises, intense odors, or other environmental stimuli may activate the body’s alarm system.

Interestingly, anxiety can sometimes arise without an identifiable trigger. In such cases, the perceived cause may appear trivial or harmless, yet it elicits intense fear and physiological responses. This illustrates the subjective and individualized nature of anxiety.

Coping with Suppressed Anxiety

The way individuals respond to anxiety triggers varies significantly.

-

For some, directly confronting the source of anxiety helps reduce its intensity.

-

For others, confrontation can amplify the sense of fear.

Therefore, it is crucial to develop personalized coping strategies that align with one’s emotional patterns and psychological needs. Such strategies might include:

-

Therapeutic support (especially cognitive-behavioral therapy)

-

Mindfulness practices to enhance present-moment awareness

-

Relaxation techniques such as controlled breathing or grounding exercises

-

Healthy lifestyle adjustments, including regular exercise and adequate sleep

Conclusion

Anxiety is an integral part of human existence—a natural and adaptive system designed to protect us from danger. Yet, when this system becomes overactive or prolonged, it transforms into a disorder that impairs mental and physical well-being.

Its causes are multifaceted, involving biological processes, environmental stressors, personal traits, and behavioral habits. Thus, the key to recovery lies in understanding one’s unique anxiety patterns and developing tailored coping mechanisms that restore internal balance.

There is no single universal method to manage anxiety—each person must find their own equilibrium. The journey toward healing begins not by fighting anxiety, but by listening to its message and transforming it into self-awareness.

References

-

Kring, A. M., & Johnson, S. L. (2015). Abnormal Psychology: The Science and Treatment of Psychological Disorders.

-

Şahin, F. (2017). Physiological Reactions in Anxiety Disorders.

-

Geçtan, E. (1978). Psikodinamik Psikiyatri: İnsan Davranışlarının Psikodinamik Temelleri.