From time to time, we may find ourselves questioning our relationship with our romantic partner. Although we actually provide a considerable amount of interest and value to them, we may observe that they become distant from us and display colder behaviors. In these moments, we may feel uneasy and perhaps think that if we become more self-sacrificing, they may not behave in this way. Thus, we may feel that we are unable to get out of the cycle and believe that it cannot be changed. In such situations, the attachment style we established with our caregiver during the early years of life can, in fact, offer us an important clue. Examining our own attachment style together with the attachment style formed by our romantic partner, and addressing this within the therapy room, allows us to view the functioning processes of this cycle from a different perspective, enabling us to take steps to transform our romantic relationships in a way that contributes positively to our psychological health and functioning, and to direct the cycle in which we feel trapped toward a different direction.

The Foundations Of Attachment Theory And Childhood Development

As human beings, in order to survive after birth, we are required to form a strong and emotionally close bond with our caregivers. According to attachment theory, through early childhood experiences with caregivers, infants develop a strong attachment, which enables them to form self-schemas and cognitive schemas about others. Research indicates that these cognitive schemas persist throughout the lifespan (Kılıç & Kümbetlioğlu, 2016). Considering the studies conducted on this topic, the attachment formed with caregivers during the early stages of life significantly influences romantic relationships and social relationships in adulthood (Hazan & Shaver, 1987).

According to attachment theory, the relationship between the infant and the caregiver may be reflected in later life in ways that result in either clingy attitudes toward others or avoidance of others in social relationships, particularly in cases where the caregiver displays neglectful behaviors, abandons the infant, excessively meets the infant’s needs, or does not allow the infant to engage in separation behavior (Arı, 2021). To briefly explain separation behavior, Bowlby (1973) stated that while the emotional bond that a newborn must establish with the primary caregiver is essential, this necessity decreases as the infant begins to walk and enters a period of exploration of the environment. Thus, the infant develops a new need: separation from the caregiver (Arı, 2021). If the caregiver inhibits the infant’s separation behavior or does not serve as a secure base, the infant may experience difficulties during the separation process, or the separation from the attachment figure may result in negative outcomes (Bowlby, 1973).

Classifying Early Childhood Attachment Patterns

Attachment styles consist of three categories. These three categories were identified by Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, and Wall (1978) as a result of their studies. These are secure attachment, anxious-ambivalent attachment, and avoidant attachment styles.

Secure Attachment Style: Individuals with secure attachment become anxious when their primary caregiver leaves their side; however, they experience relief when the primary caregiver returns.

Anxious-Ambivalent Attachment Style: Individuals with anxious-ambivalent attachment display intense anxiety and become stressed and angry when their primary caregiver leaves the environment. When the primary caregiver, namely the attachment figure, returns to the environment, they are unable to feel relieved and exhibit an intensely clingy attitude toward the primary caregiver.

Avoidant Attachment Style: Individuals who fall into the category of avoidant attachment do not exhibit high levels of reaction when separated from the primary caregiver, and when reunited, they do not display close behaviors toward the caregiver; additionally, they do not expect closeness.

The Effect Of Attachment Style On Romantic Relationships

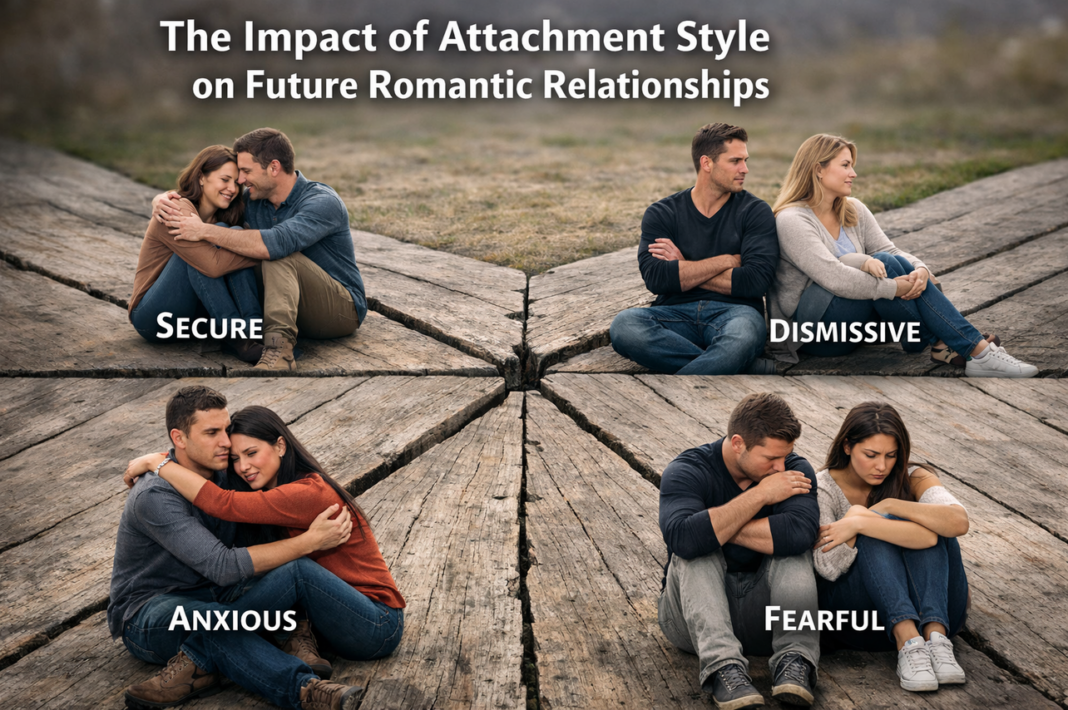

When examining attachment styles in the romantic relationships we will form in the future, it is highly important to focus on adult attachment styles. In this context, the model addressed is Bartholomew and Horowitz’s (1991) Four-Category Attachment Model. This model consists of four elements: secure, preoccupied, dismissive, and fearful attachment styles. These attachment styles emerged from the examination of two dimensions: the self and others. Both the self and others may be perceived either positively or negatively.

In the secure attachment style, there is a positive model of the self and a positive model of others. Individuals with this attachment style hold the belief that “I am worthy of love” and feel comfortable establishing closeness. In the preoccupied attachment style, a negative model of the self and a positive model of others are present. These individuals place very little value on themselves, do not avoid closeness in relationships, and may even display clingy behaviors. They constantly attempt to prove themselves in their relationships, and such behaviors may not be perceived positively by others, potentially leading others to distance themselves from them. In the dismissive attachment style, a positive model of the self and a negative model of others are present. These individuals distance themselves from close relationships in order to protect themselves. Lastly, in the fearful attachment style, both a negative model of the self and a negative model of others are present. These individuals have very low self-worth and hold negative beliefs about other people, viewing them as untrustworthy; therefore, they fear close relationships (Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991).

Avoidance characteristics are common among adults with dismissive or fearful attachment styles. Avoidant individuals are more inclined to end relationships and are more prone to engage in one-night, loveless sexual encounters (Myers, 2021).

Implications For Adult Relational Dynamics And Health

In this article, both the adult and early childhood versions of attachment theory were addressed. As a result of the review, it was found that individuals with secure attachment tend to experience more positive outcomes in various types of relationships, such as romantic and social relationships. These individuals are generally those who do not experience difficulty in forming relationships and do not create difficulties for others, both within the four-category model and in other studies. Individuals with anxious-ambivalent attachment experience communication that is much more painful and challenging compared to securely attached individuals. They may overwhelm their partners and display clingy behaviors, and they may not have healthy relationships with their romantic partners. Individuals with avoidant attachment, on the other hand, tend to avoid all forms of close relationships. They may experience trust issues, and even if they engage in a relationship, it may fail to progress in a healthy manner due to their lack of interest, emotional unresponsiveness, and fear of closeness. For this reason, becoming aware of one’s attachment style may have the power to change the direction of relational dynamics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the early bonds we form provide a blueprint for our future. By understanding these patterns, individuals can move toward more secure connections.