Even when we think we’re doing nothing, our minds work relentlessly. Whether getting ready for sleep, taking a shower, or watching the outside world from the window… While the outside world seems calm, thoughts race through our inner world. Many people describe this as “overthinking” and complain about it. However, psychology tells us that the mind’s inability to stay silent is not a disorder; it’s a natural consequence of being human.

The brain evolved not for silence, but for constant scanning. For our ancestors, anticipating dangers in the environment, visualizing possible scenarios, and predicting the future were key to survival. Although physical threats have largely diminished today, this habit of the mind hasn’t changed. Only the form of the dangers has changed: now, social relationships, performance anxieties, future plans, and “what if?” questions are at the center of our thoughts.

The Brain Was Never Designed For Silence

Neuroscience explains this phenomenon with the concept of the Default Mode Network. This network activates when the brain isn’t focused on an external task. Thinking about past memories, making plans for the future, evaluating ourselves, and making sense of emotional experiences are among the basic functions of this network. In other words, when our minds are idle, they don’t rest; on the contrary, they begin to work inward.

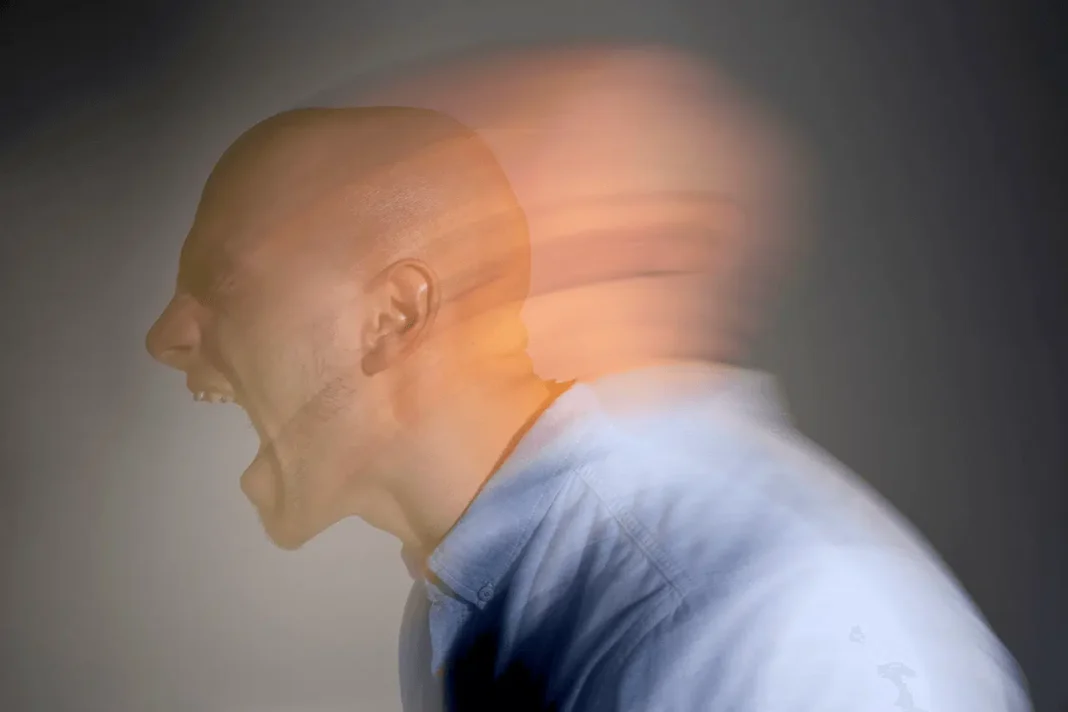

So why does this situation sometimes become tiring, even overwhelming?

When Thinking Turns Into Exhaustion: Rumination

The problem isn’t thinking itself; it’s the repetitive and unresolved cycle of thoughts. In psychology, this is called rumination. Rumination is not about thinking about a subject, but rather about repeatedly mulling over the same thought in the mind. It doesn’t produce solutions or progress; instead, it keeps the person stuck. Questions like “Why did this happen?”, “I wish I hadn’t done that,” and “What if it happens again?” are the most familiar examples of this cycle.

Why Suppressing Thoughts Backfires

The ironic thing is: the more we try to silence the mind, the more the thoughts increase. The moment we say, “I shouldn’t think about this,” the mind starts to check on that thought more frequently to control it. In psychology, this is explained by the theory of ironic processes. Thoughts that are suppressed return to the mind stronger and more persistent. Therefore, mental silence is not a matter of willpower; the more you try to suppress it, the harder it becomes.

Anxiety And The Never-Ending Alarm System

Another important factor that fuels the mind’s inability to be silent is anxiety. Uncertainty is a disturbing state for the human mind. The mind constantly generates possibilities to regain a sense of control. This leads to an increase in the number of thoughts. As anxiety increases, the mind talks more; and as the mind talks, anxiety increases even more. Thus, the person begins to experience their mind as a never-ending alarm system.

Mental Noise As A Creative Resource

However, it is important not to miss a crucial point here: the mind’s inability to be silent is not only a negative trait. The same system forms the basis of creativity, insight, and problem-solving skills. Many creative ideas emerge when the mind is freely roaming. This “idle work” state of the brain makes it possible to establish new connections and develop different perspectives. In other words, mental activity, when managed correctly, can become a powerful resource.

So, What Can We Do?

Our biggest misconception about the mind’s inability to be quiet is that we think we need to silence it completely. However, psychology tells us that instead of trying to silence the mind, changing our relationship with it is far more effective. Because thoughts are like uninvited guests; they become more persistent when they are chased away.

Reframing Mental Noise

The first step is not to view mental noise as a personal failure. The thought, “There’s something wrong with me,” only amplifies the mind’s voice. Yet this flow of thought is part of the brain’s natural functioning. The difference begins here: seeing thoughts as mental activity, not a threat.

Creating Distance From Thoughts

Secondly, putting a little distance between ourselves and our thoughts is effective. When the mind says, “What if it happens again?”, instead of arguing with it, it’s enough to realize, “Right now, my mind is generating possibilities.” This approach separates thought from reality. Not every thought is true; some are simply the voice of the mind.

Giving The Mind A Time And Place

Another effective method is to let the mind speak at the right time. Thoughts suppressed throughout the day often surface at night when one goes to bed. Instead, creating a designated short “thinking time” during the day is more effective. For example, allowing the mind to think freely for 15 minutes can reduce uncontrolled outbursts. The mind calms down when it feels heard.

The Body–Mind Connection

Bodily regulation is also far more effective than we realize in dealing with mental noise. Insufficient sleep, irregular eating habits, and inactivity raise the mind’s alarm level. The mind is not independent of the body; expecting the mind to calm down before the body calms down is often unrealistic.

Mindfulness Without The Pressure Of Silence

Mindfulness-based approaches can also be an important tool here. However, the goal of these practices is not “not thinking at all.” The aim is to be able to observe thoughts as they come and allow them to pass. Noticing a thought coming and going prevents it from dragging us along.

Listening Instead Of Silencing

Finally, it’s important to remember that mental noise sometimes signals a need. A need for rest, setting boundaries, expressing emotions, or seeking support… The mind may not want to be silenced; perhaps it wants to be heard.

Our minds slow down not when they are silent, but when they are understood.

Silence is not a goal; it is a byproduct.

Source

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Smallwood, J., & Spreng, R. N. (2014). The default network and self-generated thought: Component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1316(1), 29–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12360

Mason, M. F., Norton, M. I., Van Horn, J. D., Wegner, D. M., Grafton, S. T., & Macrae, C. N. (2007). Wandering minds: The default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science, 315(5810), 393–395. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1131295

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504

Smallwood, J., & Schooler, J. W. (2015). The science of mind wandering: Empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 487–518. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015331

Wegner, D. M. (1994). Ironic processes of mental control. Psychological Review, 101(1), 34–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.101.1.34

Zhu, X., Zhu, Q., Shen, H., Liao, W., Yuan, F., Rumination, S., & Hu, D. (2020). Rumination and the default mode network: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. NeuroImage, 206, 116344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116344

Chou, T., Deckersbach, T., Hooley, J. M., & Dougherty, D. D. (2023). The default mode network and rumination in individuals at risk for depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 324, 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.036