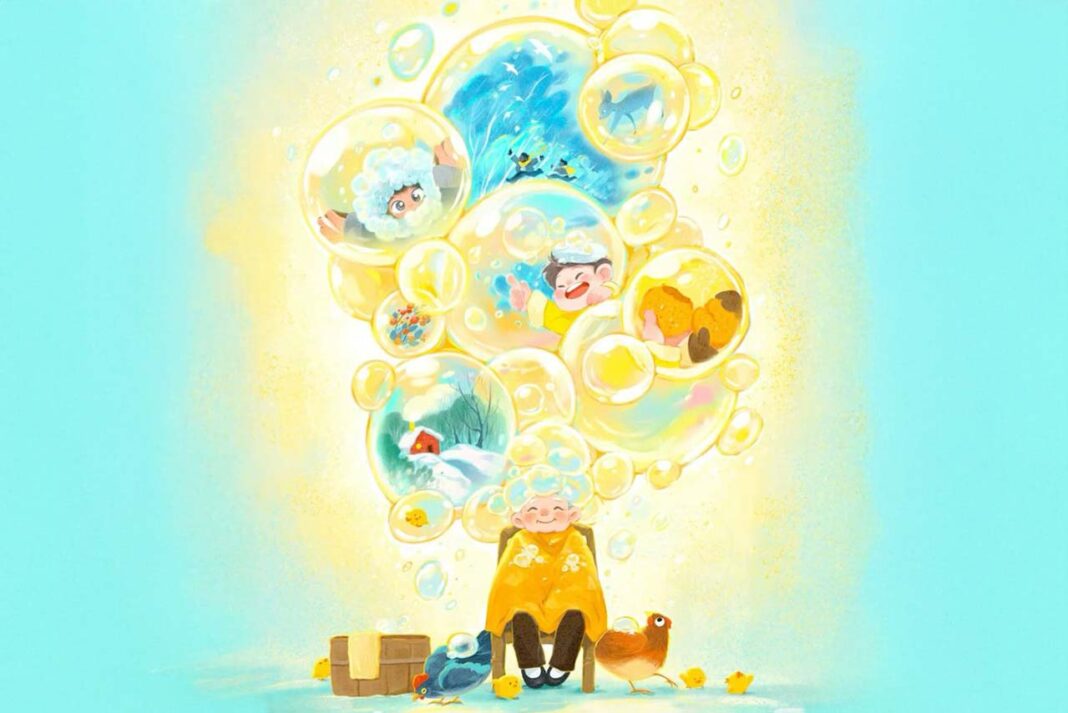

Nostalgia has a strange way of finding us. Sometimes it’s in a song we haven’t heard in years. Sometimes it’s in the smell of a place long gone. In psychology, nostalgia is defined as a sentimental longing for the past, a bittersweet emotion that blends warmth with a sense of loss that pulls you into a reverie.

Adam is one of those people who feels its pull.

Lately, he’s been going through a stressful period: deadlines piling up, life feeling uncertain, everything demanding more than he has the energy to give. In the middle of all this, he keeps drifting back to his exchange semester in Turkey. The memories sweep over him with a strange, comforting warmth. He remembers the long walks through lively streets, the late-night laughter with friends, even the smell of cigarette smoke (something he never liked) now sends him tumbling back into a version of life that feels simpler, lighter, somehow better.

Day after day, Adam finds himself walking through nostalgia more than his actual present. Until one afternoon, the sentimentality pauses long enough for him to realize…

Yes, those moments were beautiful – but the past wasn’t as perfect as nostalgia wants him to believe. He remembers the charming walks, but not the stress of the paperwork that pushed him outside in the first place. He remembers the friendships, but not the loneliness he felt in between. He remembers the sunsets, but not the uncertainty that encompassed most of those days.

So, why does the brain do this? Why does nostalgia highlight the glow and soften the rest, making imperfect chapters feel golden in hindsight?

The Adaptive And Cognitive Nature Of Nostalgia

Nostalgia functions as an adaptive psychological mechanism, particularly during periods of loneliness, uncertainty, or disruption to self-continuity (Cao, 2024). By mentally reconstructing meaningful past experiences, individuals create a narrative bridge between their past and present selves, supporting what researchers call “global self-continuity” (Hong, Sedikides, & Wildschut, 2022). This reconstruction involves cognitive processes such as selectively highlighting moments of connection, growth, or purpose, idealizing events to emphasize emotional relevance and symbolically recreating social bonds when real-life connections are absent (Cao, 2024). Through these narrative and symbolic strategies, nostalgia helps to restore a sense of belonging, reinforce identity coherence, and provide psychological grounding – not because the past was perfect, but because recalling it meets the present psychological needs for meaning, stability, and social connection.

Neuroscience: Why Remembering Feels Good

When we recall nostalgic memories, the brain’s memory center, the hippocampus, works in tandem with reward regions such as the ventral striatum and medial prefrontal cortex to generate a sense of pleasure or emotional “glow” as we remember (Oba et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2022). These reward regions, usually involved in signaling pleasure from food, social connection, or achievements, are activated during nostalgia to mark certain memories as emotionally valuable, effectively turning remembering into a rewarding experience that can lift mood and provide comfort.

This effect is closely tied to how autobiographical memory – our memories of personal life events – functions. Rather than replaying events like a neutral video, autobiographical memory is selective and reconstructive. It emphasizes details that are personally meaningful, emotionally significant, or identity-relevant, while downplaying negative or mundane aspects. This selective reconstruction allows the brain to weave coherence and emotional meaning into our personal narrative, amplifying the positive elements that give nostalgia its characteristic warmth.

The stronger the connection between memory and the brain’s reward system, the more uplifting the experience becomes. Yang et al. (2022) found that nostalgia also engages networks linked to social connection and self-reflection, helping us feel emotionally anchored and more connected to both our past selves and others. Through this interplay, nostalgia allows us to savor personal meaning, integrate life experiences into a comforting narrative, and soften the rough edges of imperfect memories.

Closing Thoughts On Nostalgia

Nostalgia is one of the ways our brains care for us. It brings warmth by highlighting the good in our past. Memories feel bright because the mind naturally focuses on what nourished us, gently downplaying the mundane or hard parts. This doesn’t mean we’re escaping reality; it’s simply how we find comfort and meaning. The moments we long for were real, but they were never the full picture. And right now, in the ordinary flow of today, new memories are forming — the same imperfect memories that may one day evoke the warm nostalgia we crave so much.

Nostalgia isn’t about wishing for a perfect past; it’s about appreciating the pieces of life that touched us without losing sight of the present we are creating.

References

Cao S. (2024). Emotion and cognition: on the cognitive processing model of nostalgia. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1440536. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1440536

Hong, E. K., Sedikides, C., & Wildschut, T. (2022). How Does Nostalgia Conduce to Global Self-Continuity? The Roles of Identity Narrative, Associative Links, and Stability. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(5), 735–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211024889

Oba, K., Noriuchi, M., Atomi, T., Moriguchi, Y., & Kikuchi, Y. (2016). Memory and reward systems coproduce “nostalgic” experiences in the brain. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(7), 1069–1077. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsv073

Yang, Z., Wildschut, T., Izuma, K., Gu, R., Luo, Y. L. L., Cai, H., & Sedikides, C. (2022). Patterns of brain activity associated with nostalgia: A social-cognitive neuroscience perspective. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(12), 1131–1144. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsac036