Losing someone we love is an integral part of the human experience. When this happens, the brain is forced to do something particularly difficult: update its expectations. Our brains must gradually rewire the assumption that our deceased loved one will eventually return. Grieving is the slow and painful process of adapting to the reality that we will never see the person we lost again.

For most people, this adaptation unfolds over time. Emotional pain softens, and memories of the deceased become integrated into daily life rather than overwhelming it. But for some, grief does not resolve. Instead, it becomes stuck.

This is where Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD)—also known as complex grief—enters the picture.

What Is Complex Grief?

Complex grief presents as a distinct psychopathology across multiple domains. It is defined by persistent and intrusive grief lasting beyond the expected period of adaptation and is associated with a relative inability to disengage from loss-related stimuli (O’Connor & Arizmendi, 2014).

Several researchers have demonstrated that complex grief is distinct from major depressive disorder (MDD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Simon et al., 2007; Prigerson et al., 2009). It is officially recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) as Prolonged Grief Disorder.

According to DSM-5-TR, symptoms include persistent yearning for the deceased, emotional numbness, identity disruption, difficulty imagining a future, and a sense that life has lost its meaning. These features distinguish PGD from normal bereavement, PTSD, and MDD, each of which involves grief-related distress but exhibits distinct neurobiological patterns (Bryant, 2018).

Emerging research increasingly supports the idea that complex grief has its own unique impact on brain systems.

How Does PGD Affect The Brain?

Neuroscience suggests that PGD reflects a disruption in the brain’s attachment and emotion-regulation systems.

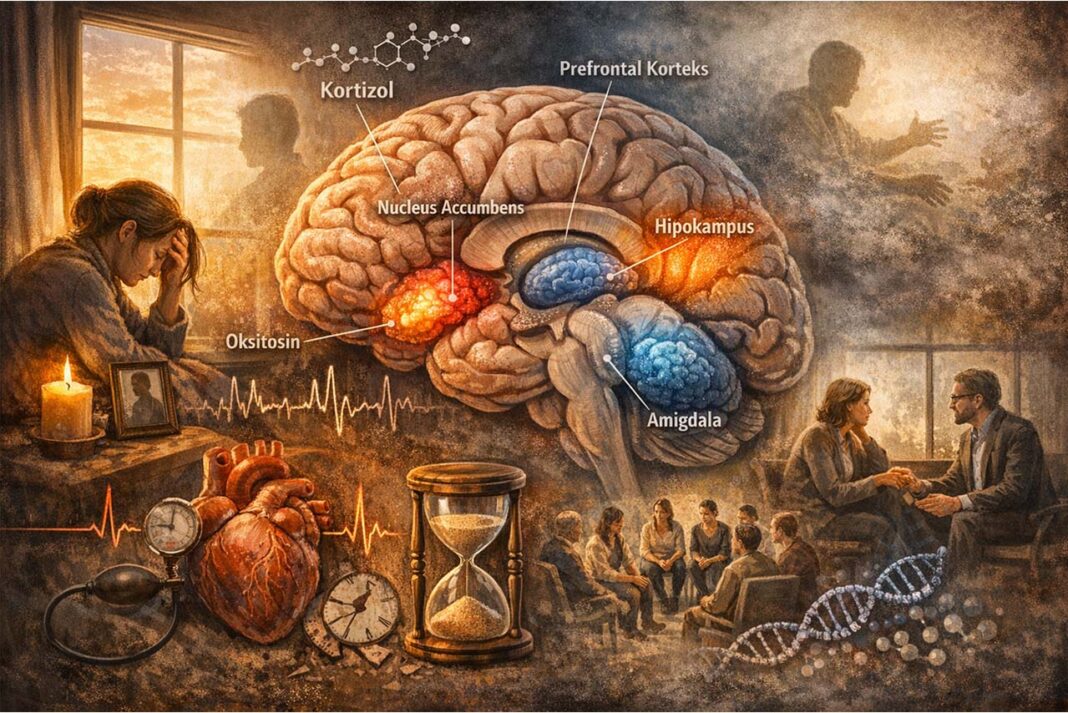

One of the most striking findings involves the nucleus accumbens, a region typically associated with reward and desire. When individuals with complex grief view photos or reminders of the deceased, this region becomes highly active—similar to patterns observed in addiction (O’Connor et al., 2008). The attachment signal remains powerful rather than fading, producing a craving-like yearning for the lost person.

At the same time, regulatory regions struggle to perform their tasks. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and parts of the prefrontal cortex (PFC), which normally help regulate distress and shift attention, show reduced or inefficient activity (Silva et al., 2014). This makes it more difficult to disengage from grief-related thoughts and emotions.

The amygdala—central to emotional salience and threat detection—tends to be overactive, amplifying sadness, anxiety, and distress (O’Connor et al., 2008). Memory systems are also affected. The hippocampus, which organizes memories in time and context, may become underactive (Grimm et al., 2009). As a result, the loss can feel ongoing and immediate rather than situated in the past.

Taken together, these findings help explain why Prolonged Grief Disorder feels so consuming: the brain continues to process the lost person as emotionally present.

Stress, Hormones, And The Body

The effects of PGD are not limited to the brain. The condition also activates the body’s stress-response system through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in persistently elevated cortisol levels. Unlike typical grief—where cortisol gradually declines—PGD maintains the body in a prolonged stress state (Mason & Duffy, 2019).

Chronically elevated cortisol is associated with memory problems, sleep disruption, immune vulnerability, and cardiovascular strain (Saavedra Pérez et al., 2017). In this way, complex grief becomes not only a psychological burden but also a physiological one.

Attachment-related neurochemistry is also altered. Oxytocin, a hormone involved in bonding, may remain elevated in PGD, reinforcing emotional attachment to the deceased (Bui et al., 2019). Rather than facilitating soothing and connection, the attachment system remains activated without the possibility of reunion.

What Helps?

Effective treatment for PGD focuses on helping the brain relearn separation and emotional safety.

Mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to reduce overactivity in the default mode network (DMN), decreasing rumination and repetitive grief-related thinking (Huang et al., 2021; Chou et al., 2023). By shifting attention from self-focused loops to present-moment awareness, these practices may support healthier neural integration.

Group therapy and bereavement support programs appear to lower cortisol levels, highlighting the protective role of social connection (Buckley et al., 2012). Social buffering may help regulate both emotional and physiological stress systems.

Researchers are also exploring interventions that directly target stress hormones and attachment circuits. While no single solution exists, neuroscience makes one point clear: complex grief is not a weakness of character or willpower. It reflects a disruption in learning and attachment systems that can, with appropriate support, begin to recalibrate.

Conclusion

Grief is a natural process of updating the brain’s internal model of the world. In Prolonged Grief Disorder, that updating process stalls. The brain continues to signal attachment, threat, and longing as though the loss has not yet been integrated.

Understanding the neurobiology of prolonged grief does not diminish its emotional depth; rather, it validates the experience. It reminds us that healing is not about “moving on,” but about gradually helping the brain learn a new form of connection—one that allows memory to coexist with life.