The idea of fate is one of the oldest and most resilient narratives of human history. Fate written by the gods in myths, the divine plan in religions, and that which is “destined to happen” in daily life. Psychoanalysis, however, brings a radical rupture to this narrative: Man produces his fate not through an external power, but through his own unconscious organization. At this point, fate ceases to be a metaphysical necessity; it becomes the result of repeating choices, repressed desires, and unresolved conflicts.

Freud And Fate As Repetition

For Sigmund Freud, man is not a rational and transparent subject; on the contrary, he is largely alienated from his own inner world. The unconscious determines the relationships, choices, and even the catastrophes toward which the subject unknowingly gravitates.

Freud’s concept of repetition compulsion (Wiederholungszwang) can be read as the psychoanalytic equivalent of the idea of fate. The individual repeatedly experiences even painful experiences in different forms; because the unconscious finds the familiar—even if painful—to be secure. In this sense, fate is not “what happens to us,” but “the scenes into which we repeatedly thrust ourselves.”

Tragedy, Repression, And The Return Of The Unconscious

The fate narratives in ancient tragedies can be re-read with this perspective. Oedipus approaches his fate the more he tries to escape it. Viewed from a psychoanalytic lens, this is the return of the repressed—returning more powerfully as it is denied.

The tragedy of Oedipus is the result of an economy of desire and knowledge operating unknowingly, rather than an absolute destiny written by the gods. Here, fate is not the absence of knowledge; it is the product of repression. Tragedy puts on stage not what man does not know, but what he does not want to know.

Lacan: Fate Written In Language

Jacques Lacan radicalizes the idea of fate even further at this point. According to him, the subject is born into language and the symbolic order. Names, laws, family structures, and social expectations draw the subject’s fate before they are even born. However, this fate is written not in the sky, but within language.

Lacan’s concept of the Real represents the most disturbing dimension of fate: a core that cannot be symbolized, cannot be put into words, but constantly imposes itself. Trauma emerges exactly here. Fate is sometimes not the event experienced; it is the fact that the event can never be fully signified—the wound left open in the psyche.

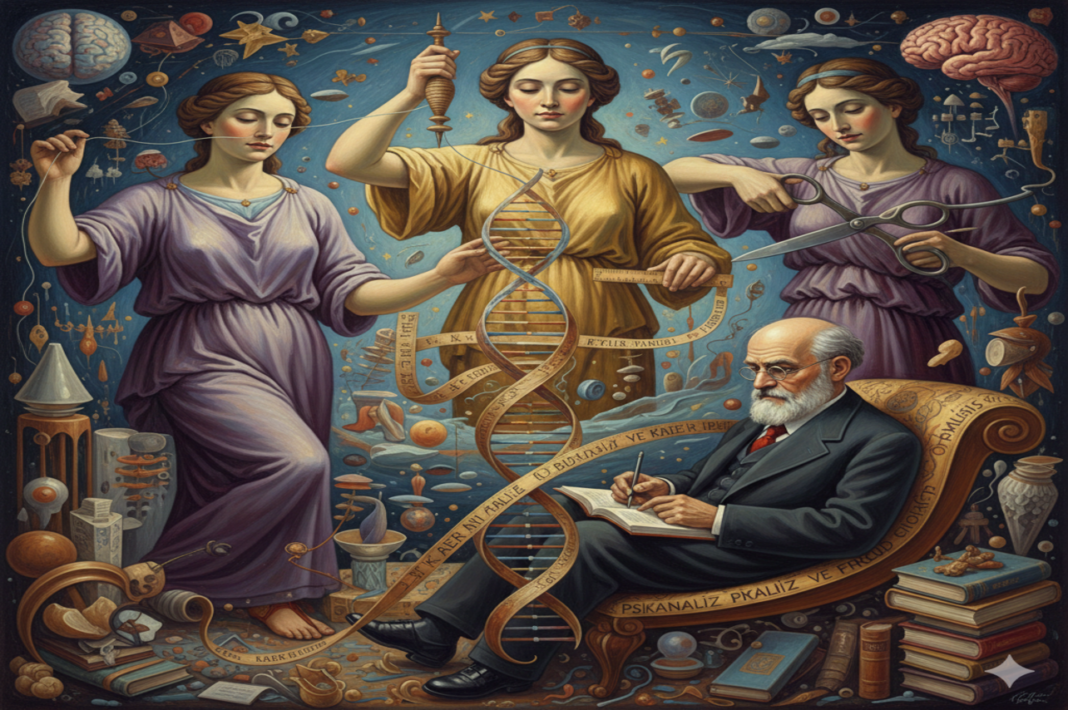

Mythology Revisited: The Moirai As Psychic Structure

At this point, mythology comes into play. The Moirai—Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos—appear in Ancient Greek mythology as the personified figures of fate. However, when handled with a psychoanalytic reading, these figures become symbols of the temporal and structural organization of the human psyche, rather than just cosmic powers.

Clotho: The Beginning Of The Thread

Clotho is the figure who spins the thread of fate; she starts life. From a psychoanalytic point of view, this represents the first network of relations the subject is placed into from the moment of birth. The bond formed with the mother, the quality of care, and experiences of love and deprivation determine the texture of the thread.

The central importance Freud gives to early childhood experiences overlaps with the mythological function of Clotho: the beginning is the moment when fate is most intensely established.

Atropos: Rupture, Loss, And Finality

Atropos cuts the thread. While being the symbol of death, from a psychoanalytic perspective she represents not only the biological end but also irreversible ruptures: traumas, mourning, irreparable losses. Freud’s death drive (Todestrieb) expresses not only the desire to vanish but also the wish for closure, termination, and a return to a state without tension. Atropos’s shears wander silently in the unconscious.

The Logic Of Repetition

What is remarkable is this: even the Moirai do not determine fate arbitrarily. They, too, are part of a larger order—just as the unconscious operates not randomly, but with a certain logic. Dreams, symptoms, slips of the tongue… They all have a repetitive pattern that seems irregular but is structured.

The threads of fate are woven by divine hands in mythology; and by the structure of the unconscious in psychoanalysis.

Fate, Freedom, And Psychoanalytic Awareness

In this context, fate is not the opposite of free will; it is an unconscious map that determines the limits of freedom. Man is not completely free, but he is not completely condemned to destiny either. Psychoanalysis does not aim to change fate, but to make visible how it is constructed.

In the analytic process, the individual begins to question their fate with questions like “Why do I always fall in love with the same people?” or “Why do I sabotage everything just when it’s going well?” This questioning does not erase destiny; but it breaks blind submission to it.

Love, Death, And The Repetition Of Desire

Love and death stand at the center of fate narratives. From a psychoanalytic point of view, love is often a re-staging of past object relations. The individual demands from adult figures what they could not receive in childhood. This is why love feels “inevitable.”

Death sometimes emerges not as the end of the subject’s fate, but as its most consistent result. Some lives flow not toward success, but toward a self-repeating destruction.

Conclusion: Fate Speaks From Within

As a result, psychoanalysis does not eliminate the idea of fate; it internalizes it. The gods fall silent, the stars retreat; the unconscious takes the stage. The Moirai descend from Olympus and settle into the subject’s history.

Fate no longer speaks from the sky, but from within the subject itself. And perhaps what is most jarring is this: Man does not choose his fate, but when he begins to recognize it, the possibility of not living the same destiny in the same way arises.

The promise of psychoanalysis is not freedom, but awareness.

And sometimes, awareness is enough to change the direction of fate.