The term “grief” is almost entirely associated with physical death in our common language and collective memory. It is widely believed that this process, in which sorrow takes the place of joy and dark takes the place of white, is a normal reaction to the physical death of a loved one. However, grieving is acknowledged in psychology literature as a universal reaction to the loss of any item or topic in which a person has invested their inner life; it is not restricted to biological death. Although Bowlby (1980) characterizes mourning as a “inevitable response to the loss of an attachment figure,” he highlights that this process encompasses not only death but also all ruptures, such as separation and abandonment. As a result, the end of a relationship can sometimes signal the start of a grief process as intense and challenging as death. Rather than the physical existence of what is lost, the meaning given to it is the main concern.

Living Absences: The Weight Of Ambiguity

At this stage, the concept of ambiguous loss becomes important, highlighting that loss is not necessarily evident or limited. According to Pauline Boss (2010), this definition describes “an open-ended situation where the loss is not physically or psychologically clear.” This form of loss can include a figure who is physically absent but psychologically present, or a person who is physically there but emotionally unavailable. Boss believes that ambiguity is one of the most difficult aspects of sorrow since the human mind desires closure and meaning.

While social rituals allow people to grieve over physical losses, this support is often missing in cases of socially unrecognized losses. While death is considered an unquestionable cause of grieving, in instances such as divorce, migration, or job loss, an individual may become estranged from their own emotions if they are unable to publicly express their suffering.

The Vanishing Mirror: Losing The Self In The Other

The relationship usually commences with a sense of “absolute continuity.” Memories etched in the mind, shared roots, and a common story all occupy a special place within us. The farewell caused by the chemistry of two people coming together creates a natural void. As a result, what is lost at the end of a relationship is often more than simply the partner. We believe we have also lost the version of ourselves as viewed through the partner’s eyes, as well as the way we interacted with that person. Stroebe and Schut’s (1999) “Dual Process Model” suggests that a grieving individual suffers with the grief of loss while also attempting to restructure their life (restoration). The weight felt during this reorganization at the end of a relationship presents itself as an understandable situation.

However, the end of a relationship is not death. Although there are times when it feels that way, when individuals find that strength within themselves and show the courage to say goodbye, they accept that they have reached the end of a story they once chose. The fundamental truth to remember is this: we once chose to welcome that person into our lives. This right to choose carries the potential to shift the direction of grief from destruction to transformation. In this process, seeking honest answers to questions such as “What did this relationship give me?”, “Which of my needs did it meet?”, “Which ones were left unanswered?”, and “Why did we reach the point of ending it?” is crucial for understanding one’s own needs.

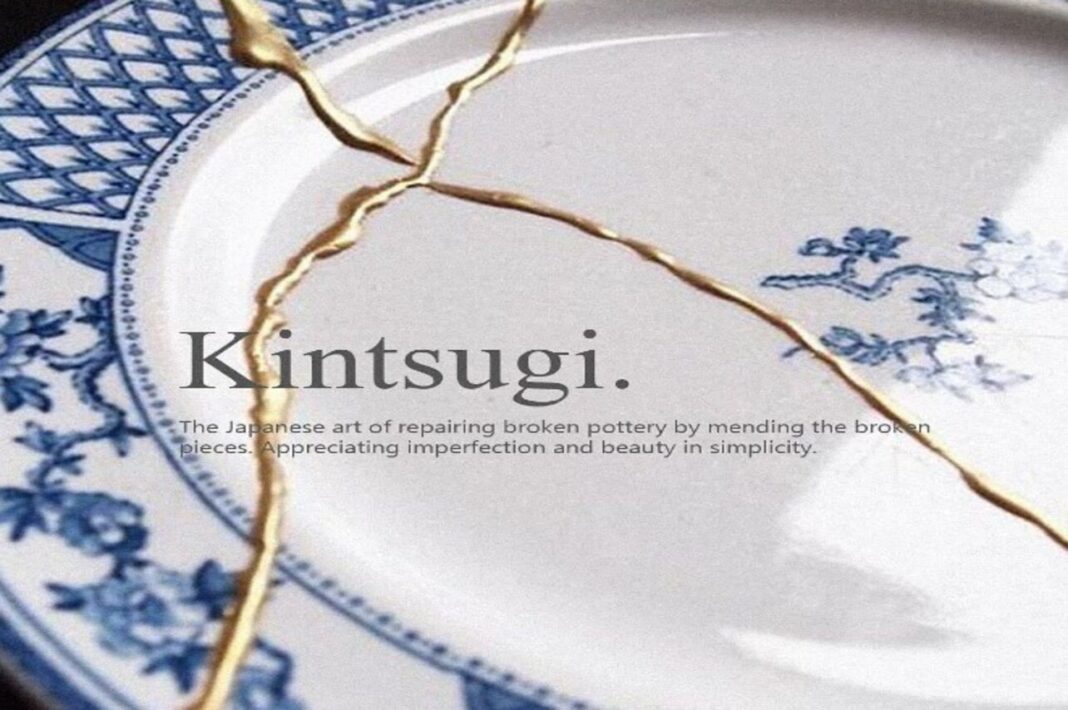

Kintsugi Of The Soul: Transforming Scars Into Strength

When a separation reaches an inevitable point, the final stage of grief is not to forget that person, but to find meaning in what was experienced. Healing begins when the individual recognizes their own expectations, vulnerabilities, and place in the relationship, rather than idealizing or ignoring it. According to Worden (2018), one of the most important aspects of overcoming sorrow is accepting the truth of the loss and moving forward by finding meaning in the pain. As a result, true healing does not come by ignoring the loss; it occurs by turning inward and reintroducing oneself to questions such, “Who am I after this relationship and what do I need today?” When the courage to look inward is shown, the farewell becomes a significant lesson that will guide the next journey.

Kintsugi, a Japanese philosophy and art form, presents a similar viewpoint on the healing process. Kintsugi is the art of repairing broken ceramic vessels using specific resin containing gold, silver, or platinum; it teaches acceptance of beauty despite imperfections and impermanence. The idea of this philosophy is not to restore an object to its pre-broken state or to hide the damage; rather, it is to understand what occurred to the piece by emphasizing its cracks with precious metals. The repaired piece is more durable and valuable than its state before it was broken because it carries the traces of lived experience.

From this perspective, feeling spiritually shattered by the end of a relationship is like a new beginning. For an individual who can turn inward during the grieving process and recognize their way of loving and their boundaries, every ending can actually be the sturdiest step toward a truer beginning.

References

Boss, P. (2010). Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Harvard University Press.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and Loss: Volume III: Loss: Sadness and Depression. Basic Books.

Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224.

Worden, J. W. (2018). Grief Counseling and Grief Therapy: A Handbook for the Mental Health Practitioner (5th ed.). Springer Publishing Company.

Would you like me to create a summary table of the four different psychological theories mentioned in the text?