The Social Nature of Domestic Violence

Domestic violence was long regarded as an individual problem confined to the private sphere; however, social science research has shown that it cannot be understood independently of social structure. Although domestic violence occurs across social classes, its form, intensity, and persistence vary according to socioeconomic conditions. In lower socioeconomic groups, economic deprivation, insecurity, and limited social support networks facilitate the incorporation of violence into everyday life. Thus, domestic violence should be addressed not merely as an interpersonal conflict but as a social problem shaped by structural conditions and power relations.

The Structural Transformation of the Family and the Patriarchal Order

Understanding domestic violence requires examining the family as a social institution. In sociology, families are classified according to criteria such as kinship relations, lineage transmission, economic structure, and settlement patterns. Within this framework, family structures are broadly categorized as traditional (extended) and nuclear families. Traditional families are predominantly patriarchal, with lineage continuing through the father, reinforcing male-centered authority and hierarchical relations. The nuclear family, composed of parents and unmarried children, has become the dominant model in modern societies. With modernization, the family’s economic production and control functions have largely shifted to external institutions, while caregiving has increasingly been shared with formal services. Despite these changes, the family’s potential to produce violence has not disappeared.

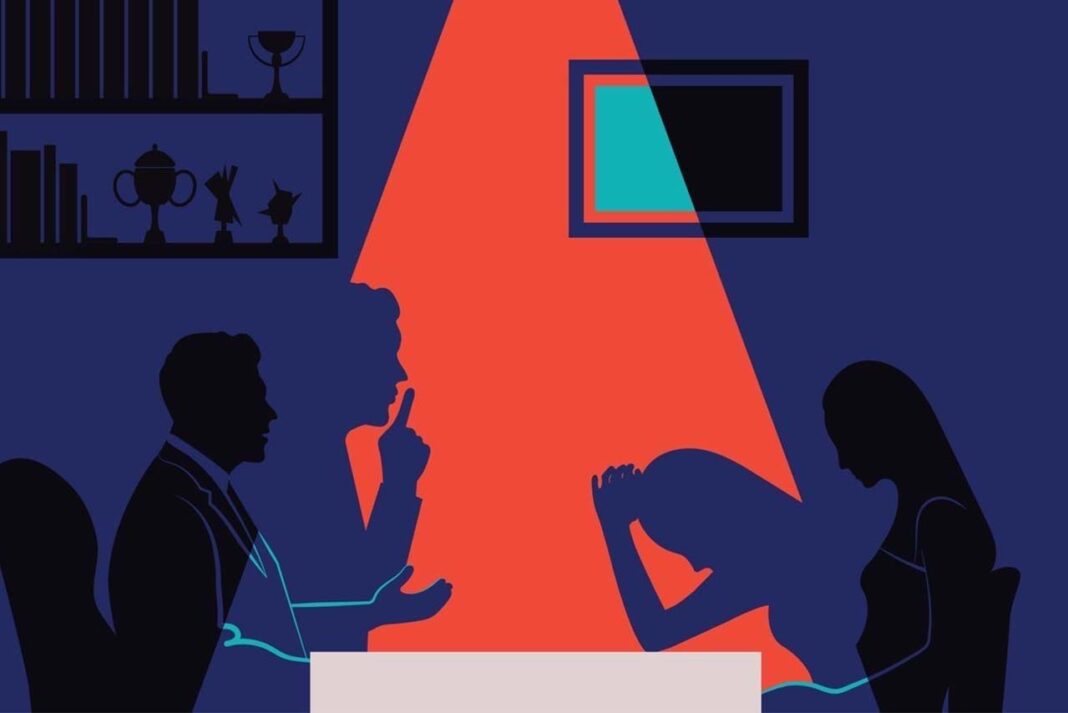

The Normalized Forms of Violence Against Women Within the Family

Women and children constitute the primary victims of domestic violence. Gender roles and patriarchal structures play a central role in directing violence toward women. Domestic violence extends beyond physical abuse and includes sexual, emotional, and economic forms that permeate women’s lives. These forms of violence often stem from men’s efforts to maintain control and reproduce power relations within the family.

Although women’s increased access to education and paid employment has altered family dynamics, patriarchy continues to shape family life. Violence manifests in multiple forms, with verbal violence being the most prevalent. Domestic violence occurs across all family types and is closely linked to control dynamics within intimate relationships. However, fear, shame, and safety concerns often prevent accurate reporting. Cultural norms emphasizing family privacy contribute to the concealment of violence. Women raised in patriarchal contexts may normalize emotional violence and internalize blame. Childhood exposure to violence, socioeconomic inequality, extended family structures, and substance use further contribute to the persistence of violence.

Socioeconomic Inequality, Education, and the Persistence of Violence

A study conducted in 2010 with women living in low socioeconomic conditions in Ankara found that illiterate women were more frequently exposed to moderate levels of violence, whereas women with a high school education or higher experienced lower levels of violence (Yaman Efe & Ayaz, 2010). It was also observed that women with better economic conditions did not experience high levels of violence. Women commonly reported that they were subjected to violence when they failed to comply with their husbands’ expectations. The perception of domestic labor as solely a woman’s responsibility, and the neglect of these duties, led women to blame themselves and accept violence. In the study, women who described themselves as “good-natured” and their spouses as “angry” had the highest rates of exposure to violence. This finding indicates that associating obedience and silence with the identity of a “good woman” contributes to the legitimation of violence.

Nationwide studies in Türkiye support these findings. A study conducted in 2008 revealed that one out of every ten women in Türkiye who had been pregnant at least once experienced physical violence by their spouse or partner during pregnancy (Tezcan, Yavuz, & Tunçkanat, 2009). More recent research indicates that exposure to any form of violence during pregnancy has increased (Durmaz & Nazlıcan, 2023). As education level rises, the prevalence of physical and sexual violence decreases. While 56% of women with no education or incomplete primary education reported experiencing physical or sexual violence at some point in their lives, this rate declines to 27% among women with a high school education or higher (Jansen, Yüksel, & Çağatay, 2009). These findings demonstrate that domestic violence is a structural problem rooted in social inequality.

Conclusion

Reducing violence in society requires abandoning modes of thought that legitimize violence. The belief that violence has a justification contributes significantly to the normalization of violence against women. At this point, women’s perceptions of which behaviors constitute violence become critically important. While derogatory expressions transmitted through written and oral culture reproduce violence, exposure to violence or witnessing violence in early life negatively shapes individuals’ conflict resolution strategies in later stages of life. Therefore, combating domestic violence must involve not only legal regulations but also the transformation of language and cultural norms that legitimize violence.

References

Durmaz, E., & Nazlıcan, E. (2023). Prevalence of intimate partner violence during pregnancy in a province of Türkiye: Changes in violence and effects on maternal mental health. Sakarya Medical Journal, 13(4), 567–577. https://doi.org/10.31832/smj.1063772

Yaman Efe, Ş., & Ayaz, S. (2010). Domestic violence against women and women’s perceptions of domestic violence. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry, 11, 23–29.

Republic of Türkiye Prime Ministry Directorate General on the Status of Women. (2009). Domestic violence against women in Türkiye. Ankara.