“We are not naturally programmed to derive meaning from the scribbles, curves, and oddly shaped letters on a page. Reading is a learned skill.”

Anne Castles, 2024

“Each instant contains more than the eye can see and the ear can hear. No experience occurs in isolation; it is always related to its surroundings, to the sequence of events that follow it, and to the memory of past experiences.”

(Kevin Lynch, 1960, The Image of the City, p. 1)

As Kevin Lynch emphasizes, the environment is not merely a physical backdrop but a mentally organized structure. For this reason, reading is not limited to decoding letters on a page; a similar cognitive process operates in our relationship with space.

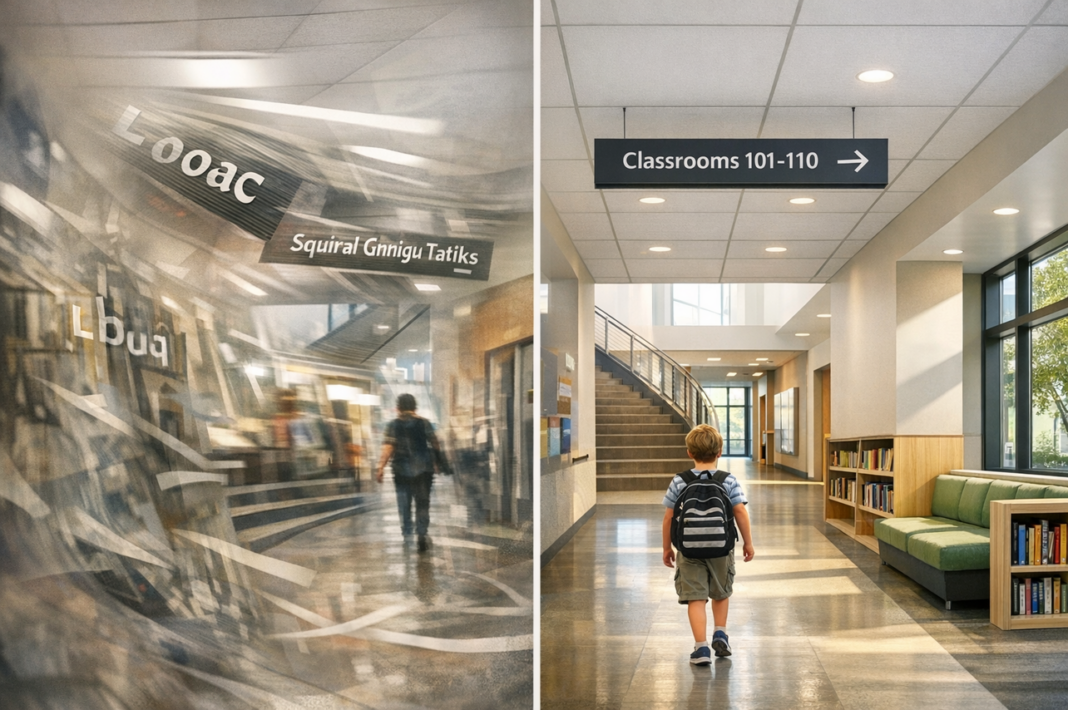

The “reading” of a space can be understood as the organization of sensory input into a meaningful whole within a mental map (cognitive map: the internal representation of the environment). Just as we comprehend a text by arranging letters and words in sequence, we navigate space through boundaries and salient focal points (landmarks: reference elements). When a structure presents a clear and coherent order, it becomes “readable.”

However, as visual complexity increases, this process becomes more demanding. In neurodevelopmental differences such as dyslexia, sensitivities within systems responsible for the temporal processing of visual information (the magnocellular system: the pathway that processes motion and rapid changes) may render spatial ambiguity more exhausting. As a result, the individual may first struggle to establish equilibrium within the environment rather than focus on learning; the environment becomes either a supportive guide or a drain on cognitive energy.

This article aims to examine the processing sensitivities inherent in dyslexia and to explore how architectural design can function as a supportive, “readable,” and inclusive tool within this fragile process.

Neurocognitive Plasticity And The Evolutionary Construction Of Reading

The human brain is not a static database across the lifespan; through neurocognitive plasticity, it continuously expands and reorganizes networks of meaning and its lexical repertoire. In a complex skill such as reading—one for which the brain was not evolutionarily preconfigured and which must be constructed through the reorganization of neural circuits—the sensitivity of this dynamic system becomes particularly visible.

This raises a critical question: How does a brain specialized for spoken language, yet not predesigned for reading, process the culturally invented skill of literacy through the coordination of neurocognitive and perceptual systems? And under which biological, environmental, and developmental conditions is this reorganization supported or rendered fragile?

The answer suggests that reading is not a single cognitive function but a holistic neurocognitive organization grounded in the coordination of multiple systems. Fluent reading emerges when visual perception, phonological decoding, attentional regulation, and semantic integration operate in temporal harmony. Reading, therefore, is not an innate faculty directly given by biology; it is a complex process of integration constructed through the restructuring of existing neural systems.

Cognitive Fragility And Automatization Difficulties In Dyslexia Profiles

Given the nature of this integration, its fragility is not surprising. A culturally constructed skill depends on both biological infrastructure and environmental support. Systematic instruction, sufficient linguistic input, and well-structured environmental conditions strengthen this reorganization; developmental differences, inadequate pedagogical support, or adverse contextual factors, however, may render the process vulnerable.

According to the neurocognitive framework proposed by Anne Castles (2024), many children with dyslexia exhibit marked difficulties particularly in grapheme–phoneme mapping processes required for decoding new words. This difficulty is not merely a temporary delay but a fundamental vulnerability that directly affects the automatization of the reading system. Some children struggle to establish stable long-term representations of encountered words. While a typically developing reader may recognize a word automatically after only a few exposures, a struggling child may need to decode the same word repeatedly each time it appears.

This reduces reading speed, as substantial cognitive resources are allocated to word-level decoding, rendering text comprehension secondary. Yet the ultimate goal of reading is not accuracy alone but meaning construction. Genetic influences may manifest in broader and more complex cognitive capacities such as memory capacity, visual processing sensitivity, and linguistic processing skills. The interaction of these systems helps explain the variability observed across different dyslexia profiles. Reading difficulties, therefore, cannot be reduced to a single cause. Multiple causal pathways exist, and disentangling them requires careful, evidence-based evaluation. Interventions directed toward the child’s specific area of difficulty—delivered with sufficient intensity and duration when necessary—yield the most effective outcomes.

A Neurodevelopmental Model: Visual Timing

Moving beyond a purely language- and phonology-based perspective, dyslexia can also be examined through a distinct perceptual lens. In his 2025 review Visual Dyslexia, John Stein reconceptualizes developmental dyslexia within a comprehensive neurodevelopmental framework that foregrounds visual timing, sequencing, and stability rather than limiting explanation to a reductionist phonological deficit model.

According to Stein, fluent reading is a dynamic process requiring the accurate sequential processing of letters and character strings with temporal precision and visual stability. In this process, the functional integrity of the magnocellular pathway plays a critical role. Developmental differences within this system may lead to reduced sensitivity in the timing of eye movements, instability in visual attentional shifts, and difficulty maintaining stability across lines of text. These challenges have been associated, in some individuals, with letter reversals, line skipping, and subjective experiences described in the literature as “visual stress.”

Stein further emphasizes that when a child first encounters written words, they are perceived as holistic visual objects, and only gradually are they segmented into sequential units. Visual sequencing processes thus develop in interaction with phonological awareness.

At the same time, Stein explicitly cautions that not every child who struggles with reading should be classified as dyslexic. Environmental variables—such as poverty, inadequate instruction, limited parental support, and broader social disadvantage—can significantly influence reading acquisition. This perspective acknowledges the heterogeneous nature of reading difficulties and avoids reducing the phenomenon to a single cognitive mechanism.

Neurocognitive reorganization always unfolds within a specific environmental and spatial context. Accordingly, the quality of learning is conceptualized not solely as a function of the child’s cognitive profile but also as dependent on the structural organization of the physical and pedagogical environment in which learning takes place.

Context Teaches: Space Determines The Quality Of Learning

A genuine developmental ground becomes possible only within an atmosphere that respects the child’s own pace of automatization, sensory profile, and especially the processing variability associated with neurodevelopmental differences such as dyslexia; an environment in which perceptual clutter is reduced, acoustic and visual balance is maintained, and the architectural setting is cognitively “readable.”

Architecture As A Supportive Environmental Regulator In The Context Of Dyslexia

As a transformative figure in architectural thought, John P. Eberhard moved the impact of spatial design on human experience beyond intuitive speculation and into the realm of empirical evidence. According to Eberhard, buildings are not merely aesthetic compositions that satisfy the need for shelter; they are “active environmental inputs” that leave measurable and lasting neural traces on the human nervous system. His vision repositioned architecture beyond its conventional boundaries, constructing an interdisciplinary epistemological ground that examines how synaptic connections in the brain are shaped by environmental stimuli.

Within this scientific framework, it has become possible to explain—through concrete neurophysiological evidence—how spatial parameters (such as ceiling height, light spectrum, or acoustic reverberation) can regulate neuroendocrine processes in hospital rooms and accelerate recovery, or optimize the efficiency of neural networks in educational settings, thereby enhancing cognitive performance and attentional capacity.

Eberhard’s perspective acquires particular significance when considering children in the process of learning, especially those who exhibit neurodiversity such as dyslexia. The child’s brain demonstrates far greater plasticity than that of adults in response to environmental stimuli. For a dyslexic child, environmental inputs are not mere “background conditions,” but cognitive loads that may either sabotage or support information processing.

When John Stein’s emphasis on visual timing and magnocellular sensitivity is considered alongside Eberhard’s architectural parameters, factors such as classroom lighting contrast, visual clutter in corridors, or the typographic clarity of wayfinding systems begin to determine the speed at which a dyslexic brain can “read” the spatial text. If the physical environment fails to respond to the dyslexic individual’s need for perceptual stability, the child expends cognitive energy simply maintaining equilibrium within the space, exhausting the cognitive reserves necessary for learning before instruction even begins.

Consequently, architectural design must be redefined not as a silent and neutral backdrop to pedagogy, but as an active neuro-environmental agent that modulates cognitive performance, regulates neurological stress levels, and biologically shapes the learning experience. When Eberhard’s scientific legacy is considered alongside the cognitive findings of Anne Castles and Stein, it becomes clear that dyslexia-friendly school design is not merely a matter of comfort, but a matter of cognitive justice.

Within this framework, architecture assumes the role of a supportive environmental modulator in the context of dyslexia—through calibrated lighting levels, controlled contrast, spatial simplicity, and intuitive wayfinding systems. An evidence-based neuro-architecture approach offers the key to constructing an inclusive developmental environment that removes environmental barriers limiting dyslexic individuals’ potential and respects the unique processing pace and style of every brain.

References

Castles, A. (2024). From language to literacy: Understanding dyslexia. Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, 157(1), 49–52.

Eberhard, J. P. (2009). Applying neuroscience to architecture. Neuron, 62(6), 753–756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.001

Stein, J. (2025). Visual dyslexia. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 12, 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-025-00316-3