Intimate partner violence (IPV) is often imagined as a physical phenomenon: bruises, broken bones, or visible fear. Yet contemporary abuse increasingly unfolds in quieter, less visible ways. Today, control does not end at the front door; it travels through smartphones, social media platforms, GPS systems, and even smart home devices. Technology has become a powerful mechanism of technology-facilitated abuse.

Recent research suggests that technology-facilitated abuse (TFA) is not an “add-on” to intimate partner violence. Rather, it represents a modern infrastructure through which coercive control is enacted, intensified, and sustained, with serious implications for survivor safety and lethality risk (Rogers et al., 2022; Reed et al., 2024).

From Coercive Control To Digital Omnipresence

IPV has long been conceptualized as a pattern of coercive and controlling behaviors rather than isolated violent incidents (Messing et al., 2021). Technology extends this pattern by enabling constant surveillance, rapid intrusion, and psychological omnipresence. Survivors report being monitored through incessant calls and messages, pressured to share passwords, tracked via location services, or humiliated through the non-consensual sharing of private images (Rogers et al., 2022).

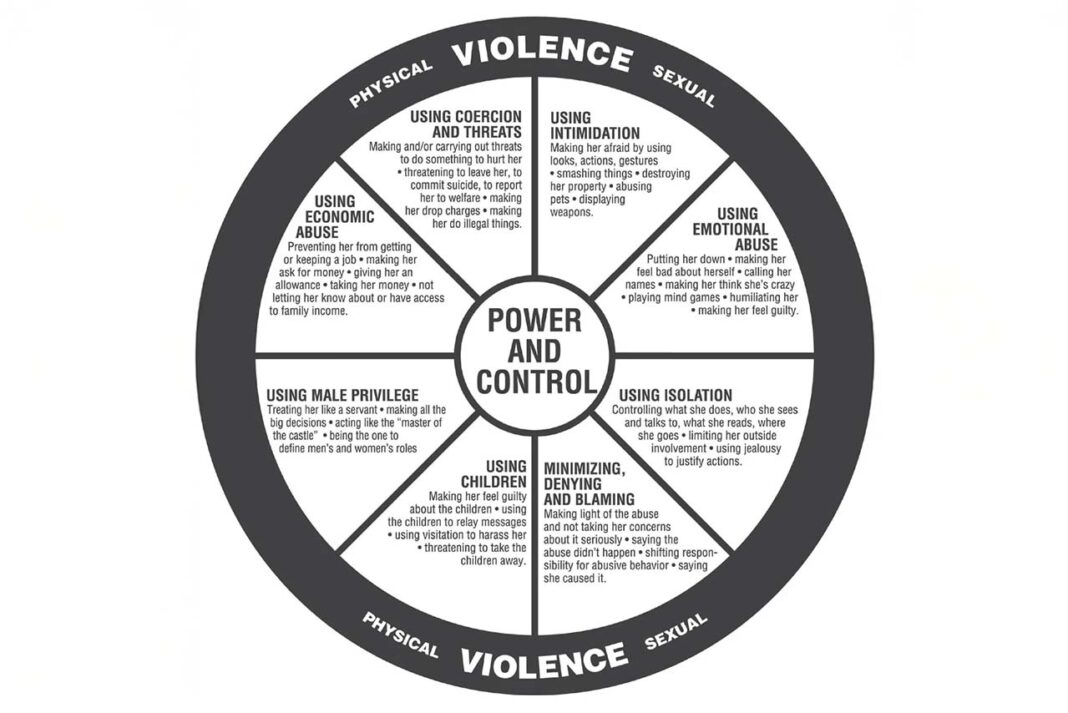

What distinguishes technology-facilitated abuse from traditional forms of stalking or harassment is not merely the medium, but its relentlessness. Abuse can continue across physical distance and time, following survivors into workplaces, social spaces, and even post-separation contexts. As Rogers and colleagues (2022) note, digital abuse often mirrors all eight domains of the Duluth Power and Control Wheel, including isolation, intimidation, coercion, and economic control.

This digital coercive control erodes survivors’ sense of autonomy and safety. Importantly, attempts to “disconnect” from technology—turning off phones or social media—may paradoxically increase risk by cutting off access to support networks or emergency resources (Rogers et al., 2022).

Patterns Matter: Moving Beyond Discrete Acts

Much of the early research on technology-based abuse focused on youth populations and measured individual behaviors (e.g., excessive texting or online harassment). However, this approach risks minimizing harm by emphasizing frequency rather than pattern, intent, and impact.

Addressing this gap, Reed et al. (2024) used a person-centered analytic approach among adult IPV survivors and identified three distinct patterns of technology-based abuse:

-

Technology-Based Emotional Abuse, characterized by humiliation, rumors, and emotionally abusive communication.

-

Technology-Based Monitoring, involving surveillance, password coercion, and device checking.

-

Technology-Based Control, the most severe pattern, combining monitoring with threats, sexual coercion, and image-based abuse.

Crucially, the most controlling digital abuse pattern was strongly associated with offline physical and sexual violence, psychological vulnerability, loss of control, and decisional conflict (Reed et al., 2024). These findings reinforce that technology-based abuse is deeply embedded within broader abusive dynamics rather than existing as a separate phenomenon.

Digital Abuse And Lethality Risk

The implications of technology-facilitated abuse extend beyond psychological harm. Emerging evidence suggests that digital control may function as an early warning marker for lethal escalation.

The Arizona Intimate Partner Homicide (AzIPH) Study highlights that most victims of intimate partner homicide experienced escalating patterns of coercive control prior to death, yet many modern risk factors—such as technology-based surveillance—are absent from traditional homicide datasets and risk assessments (Messing et al., 2021). Existing tools like the Danger Assessment were developed using data collected more than two decades ago, before the widespread integration of smartphones, social media, and smart technologies into daily life.

Messing et al. (2021) argue that contemporary IPH prevention efforts must account for firearm access, strangulation, protection orders, and technology-facilitated abuse simultaneously, as these factors often co-occur within high-risk relationships. Digital abuse, in this sense, may signal not only control but also proximity, obsession, and escalating entitlement—all of which are associated with increased homicide risk.

Clinical And Forensic Implications

For clinicians, failing to assess technology-based abuse risks underestimating the severity of a survivor’s situation. Digital monitoring may appear “non-violent,” yet its psychological impact—such as hypervigilance, fear, and paralysis in decision-making—can be profound (Reed et al., 2024). Routine IPV screening should therefore include targeted questions about digital surveillance, password coercion, image-based abuse, and online harassment.

In forensic and policy contexts, technology-facilitated abuse challenges traditional evidentiary frameworks. Surveillance apps, spoofed accounts, and proxy harassment complicate attribution and prosecution, often leaving survivors disbelieved or unprotected (Rogers et al., 2022). Without systematic data collection that captures relational history and digital behaviors, risk assessment remains dangerously incomplete.

Conclusion: Updating Our Understanding Of Abuse

Technology has not created intimate partner violence, but it has reshaped its reach, speed, and psychological impact. Intimate partner violence in the digital era requires an updated conceptual and clinical lens. Digital coercive control represents a critical frontier in IPV research, practice, and prevention.

As evidence accumulates, it becomes clear that addressing technology-facilitated abuse is not optional; it is essential for protecting survivors and preventing lethal outcomes. To move forward, research and practice must shift from asking whether technology is involved in abuse to understanding how digital control functions within coercive trajectories—and how early intervention might disrupt them.

References

Reed, L. A., Brown, M. L., Kappas Mazzio, A., Messing, J. T., Grimm, K., Wachter, K., … Gonzalez-Pons, K. (2025). Patterns of technology-based abuse among adult intimate partner violence survivors and associations with offline abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 08862605241268782.

Rogers, M. M., Fisher, C., Ali, P., Allmark, P., & Fontes, L. (2023). Technology-facilitated abuse in intimate relationships: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(4), 2210–2226.

Messing, J. T., AbiNader, M. A., Pizarro, J. M., Campbell, J. C., Brown, M. L., & Pelletier, K. R. (2021). The Arizona Intimate Partner Homicide (AzIPH) study: A step toward updating and expanding risk factors for intimate partner homicide. Journal of Family Violence, 36, 563–572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00254-9