Have you ever had a crush on someone unavailable? Maybe someone in another relationship, or worse, someone oblivious to your existence? Most of us have, or at least we know someone who has. But why is it that we so often desire what we cannot have, what always remains just out of reach? What does this reveal about the very structure of desire itself?

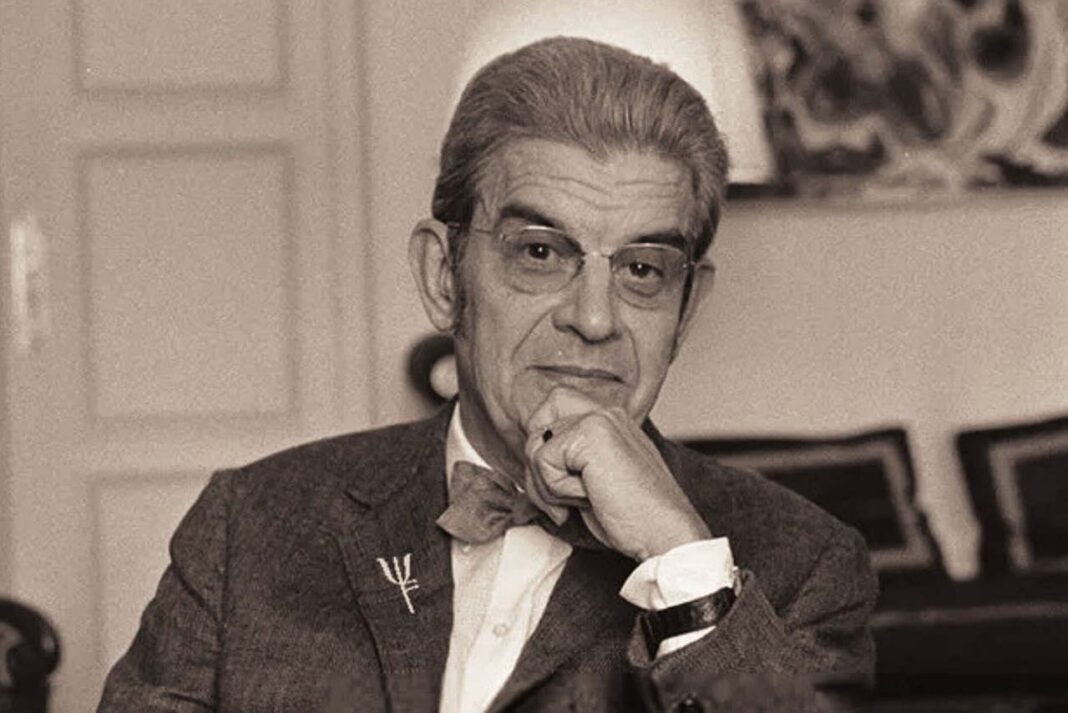

Lacanian psychoanalysis, most famous for its exploration of the mirror stage, spent much of its theoretical focus grappling with these questions. Lacan’s famous claim that “man’s desire is the Other’s desire (le désir de l’homme est le désir de l’Autre)” (Lacan, 2006/1966, p. 690) gives us a useful lens for thinking about unrequited love. What follows is only a surface-level exploration. The limits of this medium, and my own novice voice, make that inevitable. Still, I will try to sketch out how Lacan’s ideas about desire can guide us into understanding the ache of longing for someone who cannot (or will not) reciprocate.

Lacan’s Objet Petit a

The central concept that I want to focus on here is Lacan’s objet petit a (object little a). Often translated as the “object-cause of desire,” this term requires careful explanation since the objet petit a is not the object we consciously desire but rather what sets our desire in motion (Žižek, 2008, p. 53). To put it into simpler terms, when someone becomes infatuated with an unavailable person, that person themselves is not the objet petit a. Instead, the objet petit a is the indefinable quality that seems to promise fulfillment but always remains elusive.

From Jouissance to Lack

To see how objet petit a develops, we need to take a step back. Lacan argues that the subject (a child) begins life in a hypothetical state of jouissance, which is defined as an unmediated enjoyment and unrestricted drive toward satisfaction. In this early stage, the mother’s body provides a sense of fullness, what Lacan calls Das Ding (the Thing). However, it’s crucial to understand that this “original fullness” is itself a retroactive fantasy. We never actually experience such completeness, but we construct this myth to make sense of our current lack.

This state of unmediated access to the mother’s body and the sense of fullness are interrupted when the child encounters the prohibition of the “Name-of-the-Father,” which is also the father’s “No.” The father here is symbolic and has a prohibitive function as it lays down the taboo of incest onto the child, thus restricting access to the Das Ding. This “no” ushers the child into the realm of language, law, and social order. The cost of entering this symbolic order is the loss of that jouissance.

From this moment forward, the subject is defined not only by what it is but by what it lacks. The lost Thing (Das Ding) can never be recovered, but in its place emerges the objet petit a, the leftover that both covers and reveals this fundamental lack while simultaneously structuring all subsequent desire.

The Truth About Desire

This theoretical framework helps explain the peculiar logic of unrequited love. The objet petit a is not the unavailable person but rather the very impossibility of their attainment. It is the very gap their absence creates and maintains. Desire thrives on what is missing, and when the object of desire comes too close to being attained, Lacan argues that anxiety arises because the sustaining fantasy begins to collapse.

In the movie The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, Žižek captures this paradox eloquently: “A desire is never simply the desire for certain thing. It’s always also a desire for desire itself. A desire to continue to desire. Perhaps the ultimate horror of a desire is—to be fully filled in, met, so that I desire no longer. The ultimate melancholic experience is the experience of a loss of desire itself.”

Unattainable people are therefore particularly well-suited to serve the function of supporting the objet petit a: their very unavailability guarantees that the desire they create can remain safely alive. The married colleague, the distant celebrity, the friend who sees us only platonically—these figures can sustain our desire precisely because they cannot fulfill it.

From this perspective, unrequited love is not simply a personal flaw or psychological weakness. It represents the logical outcome of how desire is fundamentally structured. To attach ourselves to someone we cannot have is to engage in a fantasy that keeps desire burning while protecting us from the anxiety of actually confronting what we think we want.

References

Jancsó, L. (Director). (2012). The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology [Film]. Zeitgeist Films.

Lacan, J. (2006). Écrits: The First Complete Edition in English (B. Fink, Trans.). W.W. Norton & Company. (Original work published 1966)

Žižek, S. (2008). The Plague of Fantasies. Verso. (Original work published 1997)