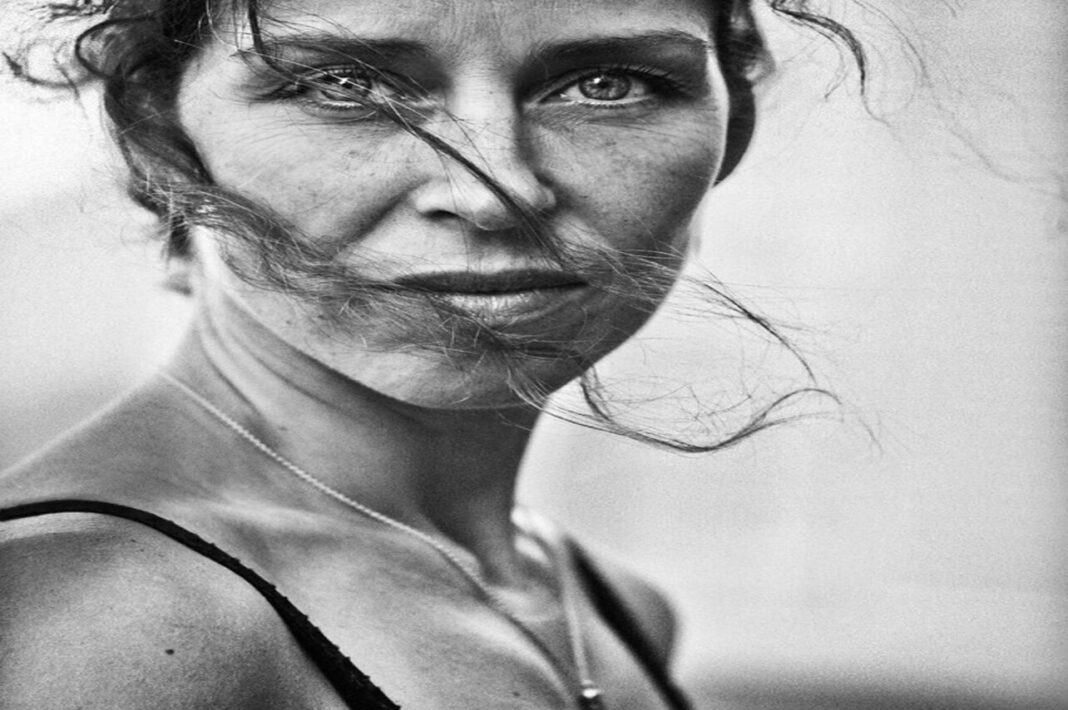

In recent years, the figure of the “strong woman” has become increasingly visible in popular culture and social discourse. The image of a woman who stands firm despite difficulties, remains emotionally stable, copes with every challenge, and supports others is often presented as a feminist achievement. However, the effects of this narrative on women’s mental health are frequently accepted without critical examination. Strength, resilience, and coping ability are undoubtedly valuable qualities, yet when these qualities are imposed on women as normative expectations, they can create a new form of pressure. Resilience narrative becomes a demand rather than a choice.

The aim of this article is to examine the dual effects of the “strong woman” myth on women’s mental health. In particular, it discusses how this narrative can function as an emotional burden, an invisible form of pressure, and a framework that makes seeking help more difficult. Drawing on feminist theory, psychology, and clinical perspectives, the article explores when the glorification of resilience shifts from being empowering to becoming harmful.

The Social Construction Of The Strong Woman Narrative

Historically, the figure of the “strong woman” emerged as a response to women’s struggle for visibility and participation in public life. In patriarchal systems, women have often been positioned as weak, fragile, and in need of protection. The strong woman narrative developed as a counter-image, aiming to highlight women’s competence and endurance. Over time, however, this figure has moved beyond its emancipatory role and has become a normative expectation.

At the social level, the strong woman is often portrayed as someone who does not cry, does not give up, handles everything alone, does not ask for help, and does not burden others with her emotional struggles. This representation risks making women’s structural inequalities and traumatic experiences less visible. When problems are framed as obstacles that must be overcome through individual resilience, broader social conditions remain unquestioned.

The Romanticisation Of Resilience

In psychological literature, resilience is defined as an individual’s capacity to adapt to stress and trauma. However, in popular discourse, this concept is often detached from its scientific meaning. For women, resilience increasingly appears not as part of a healing process but as a performance that must be constantly displayed.

This romanticised understanding of resilience praises women for “still standing” despite difficulties, while downplaying their exhaustion, vulnerability, and burnout. Statements such as “Look how strong you are” often imply that pain should be overcome quickly rather than acknowledged. As a result, women’s emotional experiences are not fully validated but are instead subtly encouraged to be suppressed.

The Obligation To Be Strong And Emotional Pressure

The widespread nature of the strong woman narrative shapes how women interpret and express their psychological distress. Within this framework, emotional struggles may not be perceived as “serious enough” or “legitimate.” Difficult experiences can be minimised by comparing them to the suffering of others. In such a context, the need to seek help may be seen as a personal weakness, while endurance and self-reliance are valued more highly.

This dynamic can lead women to place their own needs in the background and postpone seeking support. Strength becomes not only a personal trait but also a moral expectation, making it harder for women to acknowledge vulnerability without self-judgment.

The Stigmatisation Of Help-Seeking

The strong woman figure also contributes to a cultural environment in which seeking help is associated with weakness. The image of a woman who “handles everything” can make the need for psychological support invisible. As a result, women may feel internal pressure to manage their emotional difficulties on their own. This reflects a strong help-seeking stigma created by the narrative.

When asking for help appears to conflict with a strong identity, women may either suppress their struggles or seek support only when they reach a crisis point. This delay can increase the risk that mental health difficulties become more persistent and complex over time.

Internalised Resilience And Lack Of Self-Compassion

Another consequence of the strong woman narrative is that women may develop a harsher and more critical relationship with themselves. Resilience shifts from being a way of coping with external challenges to becoming an internal control mechanism. When women feel tired or overwhelmed, they may interpret this as personal failure and respond with self-blame.

In this context, self-compassion offers an important alternative framework. However, the strong woman myth may frame self-compassion as weakness or self-pity. Yet psychological well-being depends not only on endurance but also on the ability to pause, feel emotions, and receive support.

Rethinking The Narrative From A Feminist Perspective

Feminist psychology approaches individual experiences within their social context, making the limitations of the strong woman narrative more visible. Women’s experiences of burnout, anxiety, and depression should not be understood solely as individual coping failures but as outcomes of gendered social expectations.

From this perspective, the key question is not “Why are women not strong enough?” but rather “Why are women expected to be strong all the time?” The glorification of resilience should not normalise structural inequalities. Instead, there is a need for a critical framework that exposes and challenges these conditions.

Conclusion

Although the “strong woman” myth may initially appear empowering, it places significant pressure on women’s mental health. The romanticisation of resilience encourages the suppression of vulnerability, discourages help-seeking, and promotes self-criticism. As a result, women’s suffering can become invisible, and their need for psychological support may be delayed.

True empowerment for women does not lie only in the ability to endure, but also in the ability to seek support, set boundaries, and express vulnerability. Strength is not always silent endurance. Sometimes, strength means being able to say, “I do not have to carry this alone anymore.”