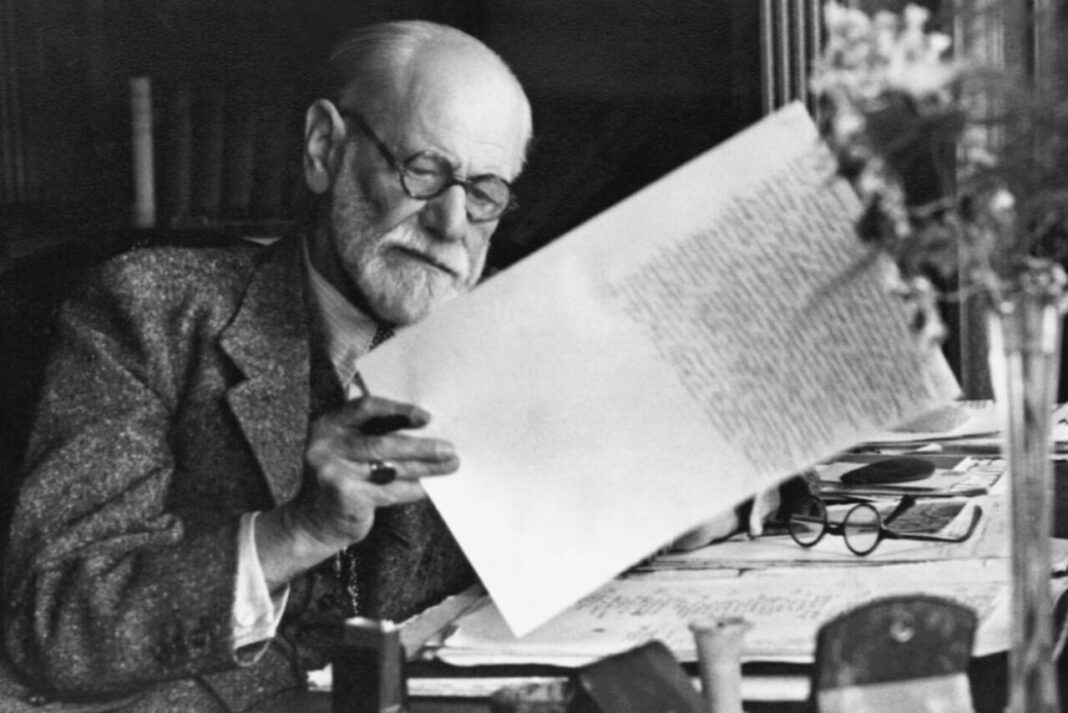

There’s someone known as the father of psychoanalysis, whose name everyone has heard at least once, and who has been the topic of many books and films: Sigmund Freud. Although many years have passed since his death, he remains the most famous person in the field of psychology. He has many theories — such as the Oedipus Complex, Infantile Sexuality, and Defense Mechanisms — which cannot be completely rejected, yet cannot be fully accepted either.

So, what is the basis of these ideas? What was Freud’s own psychology when he created these theories? Were they purely scientific insights, or reflections of his personal experiences? To understand this, it is necessary to examine and interpret Freud’s life from the beginning.

Childhood Foundations: Between Two Parents

Freud was born in 1856 in the Austrian Empire, the eldest of eight children in a financially disadvantaged Jewish family. His father, twenty years older than his mother, was harsh and emotionally distant. His mother, by contrast, was young and excessively affectionate toward him. She called him “mein goldener Sigi,” meaning “my golden boy.”

This adoration planted in Freud the belief that “Yes, she loves me, but only because I am special.” The excessive idealization from his mother created a subconscious pressure to succeed, while his deep attachment to her later became the foundation of his theory of the Oedipus Complex.

According to this concept, a child feels an intense love and devotion toward the mother, perceiving himself as her chosen one. When the child sees the mother sharing affection with the father, he perceives the father as a rival. Freud openly acknowledged this dynamic in his own life, once saying: “Knowing that I was my mother’s exact and undisputed favorite gave me a lifelong sense of victory,” and “If it wasn’t for the love and trust my mother gave me, I would have no basis for my self-belief.”

Freud’s model of personality — the id, ego, and superego — also carries traces of his family life. The id represents primitive drives and pleasure, the superego represents moral conscience and social rules, and the ego mediates between the two. His emotionally restrained father, a man who valued order and reason, likely became the psychological template for Freud’s superego.

Defense Mechanisms And The Struggle With The Self

According to Freud, the ego develops automatic, unconscious defense mechanisms — such as regression, repression, and sublimation — to reduce conflicts between the id and the superego.

Freud himself struggled with internal conflicts throughout his life. Early in his career, he experimented with substances before their harmful effects were known and initially believed them to be medical miracles. Later, even after realizing their destructiveness, he refused to admit his error. This resistance to acknowledging mistakes reflected his difficulty with self-criticism and revealed his narcissistic traits.

He also had intense disagreements with close colleagues such as Carl Jung and Alfred Adler. Jung once said, “I loved him very much, but after a while I realized that when he had an idea about something, that was the end of discussion. It was impossible to argue with him about things he really liked.” Freud claimed that those who disagreed with him were practicing “repressed resistance,” yet he himself was repressing opposing thoughts — demonstrating the very mechanism he described.

Sexuality, Sublimation, And The Birth Of Theory

Freud experienced sexuality with passion and intensity in his youth and early marriage. However, in Victorian Europe, sexuality was considered shameful and taboo. Over time, as his wife Martha began to embody a maternal role, Freud restricted his sexual expression. In his mind, the mother figure and sexual desire could not coexist — an internal conflict that stemmed from his idealization of his own mother.

He transformed this repressed sexual energy into intellectual creativity, a process he later defined as sublimation — converting unacceptable impulses into socially acceptable forms. Freud thus turned his inner conflicts into psychological theory itself.

The Oral Stage And The Habit That Never Left

Freud’s psychosexual development theory posits that infancy is dominated by the oral stage, in which sucking and mouth contact create comfort and security. Freud himself displayed a pronounced oral character — he was a constant smoker of cigars and cigarettes.

Even after being diagnosed with jaw cancer, he could not give up this addiction, confessing, “I can’t imagine a life without cigars.” His smoking habit symbolized how the id’s primitive drives overpowered the ego’s rational balance. Cigars served as a means of managing his anxiety, revealing how deeply repressed emotions shaped even his bodily habits.

A Man Who Analyzed Himself

Freud was acutely aware of his internal struggles and attempted to psychoanalyze himself through dream analysis and free association. Rather than being destroyed by his inner turmoil, he transformed it into insight. Many of his greatest theories emerged during times of personal crisis.

As Carl Jung once said, “A good healer must be wounded. A healer without wounds cannot be a healer.” Freud’s life story exemplifies this truth — his wounds did not destroy him; they became the very source of his genius.

Conclusion: The Human Behind The Theories

Freud’s theories were not born in sterile laboratories, but from the raw depths of his own psyche. His need for love, his internal conflicts, his resistance to criticism, and his transformation of pain into thought all shaped the foundations of modern psychology.

Behind every concept — from repression to the Oedipus Complex — lies a man who was, above all, his own first patient.