Do you ever feel like giving up even when you’re doing something you’re actually good at? Or find yourself wanting to quit before you’ve even started something new? That feeling shouldn’t be mistaken for laziness or lack of ability. More often than not, it might be a subtle sign of self-sabotage.

But how does self-sabotage actually work?

Self-sabotage can be sneaky. It slips into our lives through our habits, relationships, and thoughts often unnoticed. Sometimes it might show up as an inner voice whispering that “You’re not good enough.” Other times, it disguises itself as behaviors that quietly block our progress. What makes it so deceptive is that it is likely to happen beneath our awareness without us even realizing what we’re doing, even justifying it. Until you realize it’s you standing in your own way. Where some people procrastinate on an important goal, telling themselves they’ll start “when things are perfect,” others stay in unfulfilling relationships, thinking deep down they don’t deserve any better than this. To sum up, many people can experience self-sabotage as a complex mix of actions and thoughts that might disrupt personal development and achievement.

By looking deeper, we can begin to understand what lies beneath the surface of these self-destructive habits and approach it with more clarity rather than shame. If we take a look at Freud’s Beyond the Pleasure Principle, it may offer us a deep perspective on this concept (1922). Freud mentions the two instincts: life and death. While the life instinct drives us to thrive, bond, and build, the death instinct pulls us toward destruction, disintegration, and aggression. In other words, within each of us, there’s a pull toward life and another often unconscious pull toward destruction. Self-sabotage can be understood as a psychological expression of this inner conflict. It can be seen as the product of this conflict when an unconscious fear of what that growth may cost us overpowers our desire to grow.

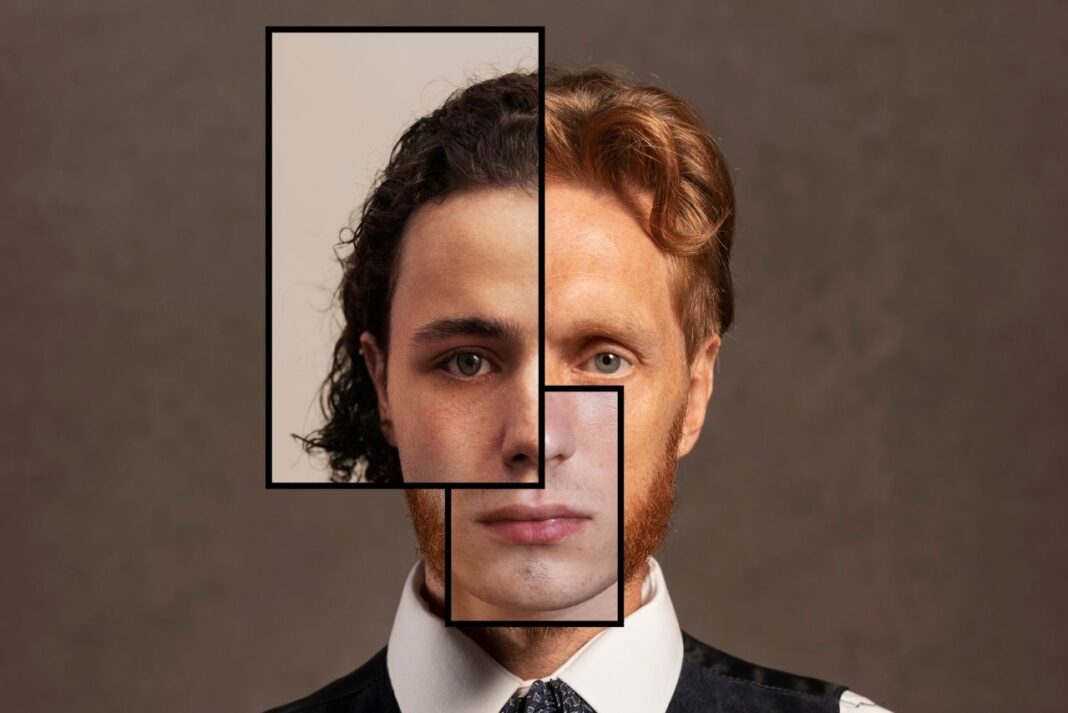

Many patterns of self-sabotage don’t come out of nowhere they often have roots in our early experiences. As children, our earliest beliefs about ourselves begin to form through our earliest relationships. Winnicott emphasized the importance of mirroring in early development the idea that a child first sees themselves through the emotional reflection of the caregiver through their face. If that “mirror” is distorted, absent, or harsh, the child may come to see themselves as unworthy, incapable, or fundamentally flawed. Over time in our lives, we absorb messages about success, failure, worth, and love, and these internalized messages can evolve into a sabotaging inner voice that repeats old patterns, not out of truth, but out of habit. What begins as a way to make sense of early emotional environments can become a lifelong script of self-doubt and fear. We might avoid risks to protect ourselves from failure or sabotage opportunities to avoid the discomfort of growth. Even though the original environment is long gone, the programming remains unless we consciously rewrite it.

Rather than seeing self-sabotage as a weakness, viewing it as a coping mechanism formed in response to earlier experiences can be a powerful reframe. Every small act of self-compassion, every pause before an old pattern, and getting help from a professional when needed may help chip away at the walls you’ve built around your own potential. Healing isn’t always dramatic or linear. Often, it begins with simply noticing when you’re standing in your own way and gently stepping aside. Sometimes, it even means allowing space for a step back before moving forward again and accepting that even regression can be part of growth.

References

Freud, S., & Jones, E. (Ed.). (1922). Beyond the Pleasure Principle. (C. J. M. Hubback, Trans.). The International Psycho-Analytical Press. https://doi.org/10.1037/11189-000