The Loss Of Innocence And The Existential Angst Of The Provincial

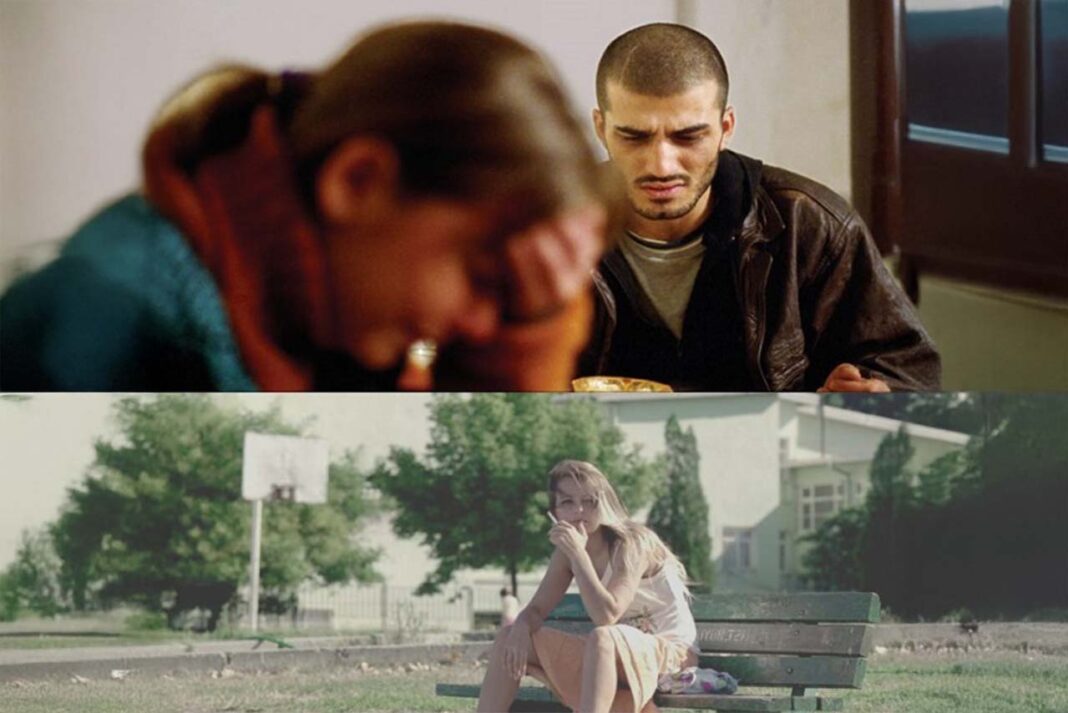

Zeki Demirkubuz’s film Kader (2006) stands in Turkish cinema not merely as a story of “impossible love,” but as one of the most shattering psychological texts filmed regarding the dark corridors of the human soul, the anatomy of Obsession, and the inevitability of an existential cycle. To view this film through the eyes of a psychologist is not simply to diagnose the pathologies of the characters, but to analyze the painful relationship the individual establishes with society, desire, and their own self—analyzing the state of a “permanent wound.”

Although the film progresses along the axis of Bekir and Uğur, there is actually a third protagonist: the confinement of space and time. Demirkubuz imprisons his characters not only in physical prisons (as in the case of Zagor) but also in mental and emotional ones. As viewers, we breathe in this sense of confinement from the very first minute of the film. This review will take the film beyond a classic “obsession” story and discuss it across a wide spectrum ranging from René Girard’s theory of triangular desire to the psychoanalytic concept of “objet petit a,” from the sociological “crisis of masculinity” to the concept of Costly Agency, which adds a new annotation to the helplessness of the characters.

Part I: The Phenomenology Of Bekir

“The Man Who Dared To Be Small” And Masochistic Freedom

The character of Bekir (Ufuk Bayraktar) appears at the opening of the film as a passive young man seeking direction, trapped in his father’s carpet shop under the shadow of the “Law of the Father.” However, the first moment Uğur enters the shop is a milestone for Bekir. This encounter is the moment where the “gaze,” as discussed by Lacan, becomes objectified. When Bekir looks at Uğur, he sees not just a beautiful woman, but “excitement,” “danger,” and “life” outside of his own boring and predictable existence.

To label Bekir simply as an “obsessive lover” would be to miss the depth of the character. Bekir is a secular and tragic reflection of Kierkegaard’s concept of the “Knight of Faith.” According to Kierkegaard, faith is believing by virtue of the absurd. Bekir renews his faith in Uğur at every point where logic, social norms, and reason say “give up.” This is not a rational decision, but an ontological leap.

Bekir’s tragedy is not that he cannot reach Uğur; Bekir’s tragedy is the reality that if he reaches Uğur, his identity will be annihilated. On a psychoanalytic plane, Uğur is Bekir’s objet petit a (the object cause of desire). This object loses its meaning when attained; but as long as it is pursued, it gives the subject a sense of “existing.” When Bekir says, “I cannot live without her,” he is actually saying, “I do not know who I am without this pain.”

Part II: Uğur And Costly Agency

Not A Victim, But A Subject Who Pays The Price

In film critiques, Uğur (Vildan Atasever) is often portrayed as a “malicious,” “exploitative,” or “drifting” woman. However, a psychological reading reveals that Uğur is the character with the strongest agency in the film. The key concept we will use here is Costly Agency.

Martin Seligman’s concept of “learned helplessness” is insufficient to explain Uğur. Uğur is not helpless. Following Zagor, working in hotel corners, keeping Bekir’s interest both rejected and yet held as a safety net—these are all choices. However, these choices are not preferences made among good options. Uğur is forced to choose between “bad” and “worse,” and every choice exacts a high psychological, social, and physical cost from her.

Society tells her, “Choose Bekir, be comfortable.” This is a comfortable but desireless life. Uğur, on the other hand, chooses “Zagor”—that is, danger and passion. This choice is not rational, but it is free. Uğur pursues her own desire at the cost of being labeled a “fallen woman” by society. This shows that the woman is not a passive victim, but an agent strong enough to risk her own destruction.

Part III: Zagor And The Triangular Desire

The Gravitational Force Of The Invisible Center

René Girard’s theory of “Mimetic Desire” is a perfect template for decoding the network of relationships in Kader. According to Girard, desire is not a straight line (Self → Object), but a triangle (Self → Model → Object).

In this triangle:

-

Subject: Bekir

-

Object: Uğur

-

Model / Mediator: Zagor

Zagor’s existence magnifies Bekir’s desire, not because Zagor is superior, but because he occupies the forbidden, dangerous, and socially excluded position. Bekir does not only desire Uğur; he desires what Zagor represents—freedom from mediocrity, violence as authenticity, and existence outside social norms. In this sense, Zagor is the invisible gravitational center of the entire narrative.

Conclusion: Destiny Or Choice?

Bekir As Sisyphus

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus says of Sisyphus, who pushes the rock to the top of the hill only to watch it fall back down every time, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” Because Sisyphus’s punishment is at the same time his existence.

At the end of the film Kader, Bekir is once again in a hotel room, once again on the road. Nothing has changed; only the lines on his face have deepened. As a psychologist, we might view this ending as an untreated pathology. However, from an existentialist perspective, this is Bekir’s victory. Bekir reconstructs what he calls destiny with his own hands every day. He is not a victim unaware of what he is doing; he is a man who, using his Costly Agency, chooses to be the hero of his own story at the cost of suffering.

Zeki Demirkubuz does not present us with healed people. He presents us with characters who exist with their wounds, who adopt their wounds as identity, and who remain human thanks to those wounds. Perhaps the greatest psychological truth the film whispers to us is this: human beings exist not to be happy, but to live their own truth; and sometimes this truth is the darkest destiny itself.