The word stress often evokes discomfort. This is understandable, given the frequent emphasis on its association with cardiovascular diseases. However, research suggests that it’s not the stressor itself, but rather the duration of the body’s response to it, that poses the real risk. If the physiological stress response continues even after the threat has passed, that’s when damage begins.

Our relationship with stress is multilayered. For example, the mild tension before an exam is our initial introduction to stress. Yet when thoughts persist long after the stressor is gone, they can prolong the body’s stress response. If such stressors occur repeatedly without proper resolution, the body enters a state of chronic stress. This cumulative impact is known as allostatic load the wear and tear on the body caused by repeated efforts to adapt to stress.

The Role of the Central Autonomic Network

The central autonomic network (CAN) is a control system that connects the brain and the heart. Through the vagus nerve, brain structures integrate with autonomic outputs, regulating heart rate variability (HRV). A healthy heart rate variability indicates that the heart is responding flexibly and adaptively to environmental stress. When this system fails to function optimally, the risk of cardiovascular issues such as heart attack, hypertension, and arrhythmia increases.

Perseverative Cognition: The Mind’s Trap

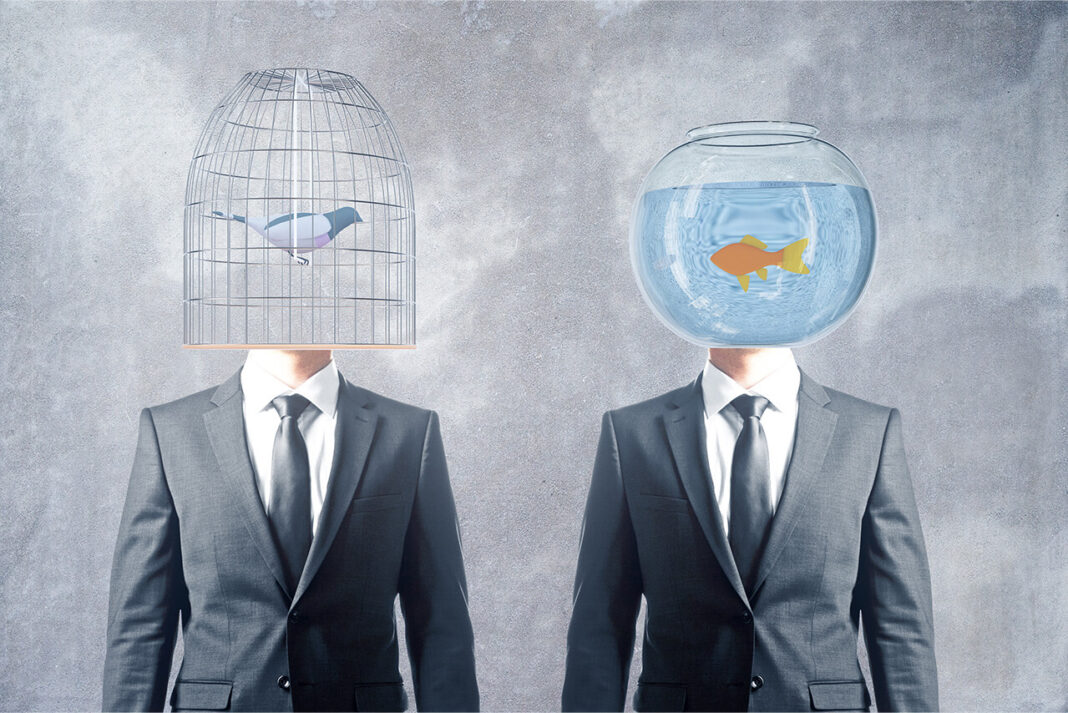

One of the key traits that distinguishes humans from other species is our ability to mentally represent events. But this capacity is also a double-edged sword. We tend to worry about things that haven’t happened yet (“what if?”) or ruminate on the past (“why did that happen?”). These cognitive patterns are known as perseverative cognition. Especially in anxiety and depression, they can become ineffective coping mechanisms. In anxiety, for instance, the person mistakenly believes that worrying is a form of preparation. Over time, however, the worry becomes a worry itself.

Sometimes, even when we are aware that we are stuck in negative thoughts, we can’t seem to break free. This may be due to weakened working memory, which makes it difficult to shift from old to new information. Additionally, impaired inhibition the brain’s ability to suppress irrelevant information may lead negative content to linger longer in memory and resist suppression.

Why Some Struggle More

Why do some individuals struggle more than others to let go of these thoughts? This is where psychological traits come into play. Strong goal commitment can prolong rumination when goals are perceived as threatened. Traits such as perfectionism, low self-esteem, and pessimism also intensify perseverative cognition.

The Social and Physical Toll of Anxiety

Anxiety has not only physical but also social consequences. When a person doesn’t feel safe, they struggle to engage in socially adaptive behavior. Still, it’s important to remember: anxiety can only take over if you allow it.

The Neurovisceral Integration Model

At this point, the Neurovisceral Integration Model offers a comprehensive framework explaining how the brain, autonomic nervous system (especially the vagus nerve), and behavior work in coordination. According to this model, the better the communication between the heart and the brain, the stronger our emotion regulation capacity. The prefrontal cortex (PFC), in particular, plays a central role in attention, planning, emotion regulation, and decision-making. When the PFC is in sync with the body, it helps downregulate the stress response. The result: a calmer heart, a clearer mind, and more control over emotions.

Strengthening the Mind-Body Connection

So, how can we strengthen this system? The answer is surprisingly simple: heart rate variability biofeedback and resonance frequency breathing. With just 5–10 minutes of breathing at a rate of six breaths per minute, you can recalibrate your mind-body system.

How to Practice Resonance Frequency Breathing:

- Inhale for 4 seconds

- Exhale for 6 seconds (especially slowing the exhale activates the vagus nerve)

This rhythm synchronizes your heartbeat and breathing. The baroreflex and RSA (respiratory sinus arrhythmia) systems support each other, increasing heart rate variability and enhancing the body’s resilience to stress. You can practice this before an exam, before sleep, or whenever you feel anxious.

Additional Techniques for Stress Relief

Additionally, we know the vagus nerve runs from the brainstem down through the neck. Therefore, applying cold to the neck area or immersing the palms in cold water can stimulate the parasympathetic system, reducing stress levels. Cold exposure creates a micro-stressor in the body, and the recovery that follows helps restore physiological balance.

Conclusion: Supporting Mind-Body Dialogue

In conclusion, the mind and body are in constant communication. The more we support and strengthen this dialogue, the better we can adapt not just to stress, but to life itself.